You’re Probably Not Going to Like This Piece

Too much nuance, not enough fist-pumping. Sorry!

Above: Donald Trump probably does not like this piece.

Hi! You’re probably not going to like today’s newsletter.

How’s that for a start to a long think piece? I can hear you now: well, if the author himself thinks I’m not going to like this, who am I to argue? [Sound of laptop closing.]

Wait! Stop! Let me explain.

I’m not saying you won’t like today’s piece because it’s boring. I don’t think it is! It’s just that it doesn’t follow the usual pattern of Substack newsletters—or, well, most online political pieces. The usual pattern is: Hello, reader! Here is a neat, easily summarized thesis, which I will now support. In fact, the lack of such a thesis is almost the point of today’s piece.

I’ve been thinking about my next Substack piece ever since I saw Jonathan V. Last’s very kind recommendation at The Bulwark of my recent Substack piece about backing away from Twitter. A lot of people subscribed based on his recommendation. I told friends of mine: “The next thing I write needs to be good.” (I didn’t add “for once” because everyone understood that’s what I meant.) And frankly, the thought has paralyzed me for a while.

And now here I go opening the piece by telling you that you’re not going to like it. Well, nobody ever accused me of being a good marketer.

As I thought about potential topics, I noticed they fell into two categories: 1) things that are obvious and therefore don’t really merit a lot of discussion, and 2) things that are more nuanced and therefore have more than one side. The latter categories—topics with nuance—tend to be the more interesting concepts to discuss, don’t they? But every time I started to write about one of them, and took a position, I thought of ways that the opposite of my position is also true . . . sometimes.

Well, why fight it? Let’s discuss some of those topics. If I have a thesis, it’s . . . well, it’s complicated. But it comes down to this: it’s very easy to take a position in favor of (or against) things like tribalism, reliance on expertise, bucking conventional wisdom, and the like. But sometimes, your intuitive position will be wrong. (And sometimes, and perhaps even often, it will be right!)

Maybe, like me, you’re a fierce critic of tribalism. In the era of Trumpist politics, who isn’t? But tribalism has positive aspects too! (We’ll get to that.) Or maybe you think it’s generally a good idea to rely on experts . . . or to buck conventional wisdom. And sometimes it is (as to both). But sometimes it isn’t (as to both).

This is not to say there aren’t topics where the answer is straightforward. There are. But today I want to discuss topics that have multiple angles and no easy answers.

Let’s dive right in. Let me warn you up front, however: this piece is nearly 3000 words. For paid subscribers, it’s nearly 8000 words, and thus too long for most email services to replicate it fully unless you click a button at the bottom that says “View Entire Message.”

My Job Is To Challenge You

If you’re reading this, the one thing I know about you is this: you are not just looking for an echo chamber. I know this as strongly as I know anything. How do I know this? Whether you’re a long-time reader or a new subscriber, whether you’re from the left or the right, I know this about you: you’re almost certainly not a member of the Trump cult.

Because the Trump cult can’t really handle newsletters like this. They get too angry.

You and I are different. We actually care about evidence.

To cite one example: if you wanted pro-Putin propaganda exclusively, you’d sign up for Glenn Greenwald’s newsletter, and/or Matt Taibbi’s, and call it a day. (No doubt a handful of you do subscribe to those folks—and that’s fine!—but if you’re also reading this, you at least suspect that theirs is not the only point of view worth considering.)

The last thing in the world I want is readers who are looking for an echo chamber. There is a corollary to that: I will never tell you things that I don’t believe, but that I say anyway because I think you want to hear them. Nothing is more boring than a writer who never challenges his or her readers. The most useless pundit in the world is the pundit who tries to figure out what the audience is comfortable hearing, and then says that thing. That does not provide a satisfactory experience for a reader who cares about evidence.

Where have we seen such a phenomenon recently? Why, I do believe we might find such an example in a company called Fox News, together with its parent company the Fox News Corporation. I am going to go ahead and assume your familiarity with the allegations of the Dominion lawsuit against these entities. There’s no point in rehashing that all here. If you have not read the Dominion brief, you can read it here. It is chock-full of evidence that officials from Fox knew, not just that the Trumpist claims of a stolen election were false, but also that they were crazy. And yet, Fox News spread those lies anyway, to “respect” their audience’s wishes to hear this garbage.

Sure, telling the audience what it wants to hear is a great way to make money. As Fox News recently learned, it’s also a great way to get sued—especially if you know that what the audience wants to hear is false, and you constantly email each other about how false and crazy those lies are . . . but you broadcast the lies anyway.

Just look at Tucker Carlson’s latest attention-grabbing nonsense, wherein he has taken isolated snippets of footage from the January 6, 2021 insurrection and tried to portray that event as a sightseeing tour. The absolutely indefensible nature of Carlson’s ridiculous presentation reflects an obvious motive: Tucker is telling his viewers what they want to hear.

You should never read or watch anyone who does that. You should only read or watch people who tell you the truth.

My Job Is To Reassure You

However, as long as I am following the cardinal rule of telling you the truth, and only offering opinions I actually believe, it’s actually a good thing for me not just to challenge you, but also to reassure you.

In fact, my original opening line for this piece went like this:

As a writer, one of my most important jobs is to reassure you, the reader, that you’re not crazy.

Again: I’m most definitely not in favor of advocating positions I do not actually believe, whether it be for clicks or subscriptions or kudos or any other reason. But if I can tell you what I actually believe, and it happens to line up with your beliefs—beliefs that you stand by, but which seem very unpopular . . . that can be reassuring.

However you came to be reading this, part of what you’re likely looking for is some sanity in an insane world; some normal-sounding opinions you agree with instead of the increasingly unhinged opinions espoused by so many in the political party or movement you used to revere.

We have a diverse readership here, BUT: you’re probably here because you’re sympathetic to, or at least open to hearing, a reasonable conservative view of the world—one that elevates the principles of people like Ronald Reagan, and deplores the behavior of people like Donald Trump. (Either that, or you are a Donald Trump superfan who made a big mistake, and will soon be looking for the unsubscribe button.)

I share that view. The things that my favorite writers do for me—here I’m talking about people like Nick Catoggio or Kevin D. Williamson at The Dispatch, or many of the folks at The Bulwark—is to reassure me that not all conservatives have gone completely around the bend.

Now that I have praised the virtues of reassuring you, let me challenge you. Tribalism is a frequent topic these days, especially for those of us who regularly discuss politics. Many of us have written pieces decrying the scourge of tribalism. We see its effects everywhere. People are turning insane, and they seem to be doing so as a sort of groupthink.

So maybe it’s time for a hot take on tribalism. It can be good! Tribalism alone isn’t what’s bad, it’s what tribalism promotes that matters.

Tribalism Can Be Bad

Before I make that case, let me pause for a moment to recognize the case against tribalism. I’m very familiar with that case. I have made it nearly every day for years now. I don’t think I have to belabor the point. If you’re here, you probably already know the dangers of tribalism.

We see the evidence all around us, all day, every day. As I say, the Republican party has largely gone well and truly insane. Trump may be indicted this coming week, and conventional wisdom says that if he is, that is likely to cement his nomination. He has called for protesters to show up if he is arrested. In other words, he is potentially summoning a mob the way he did on January 6. Nobody in Trump world seems to care. They enforce conformity in Trump world very very strongly. So strongly, and also powerfully.

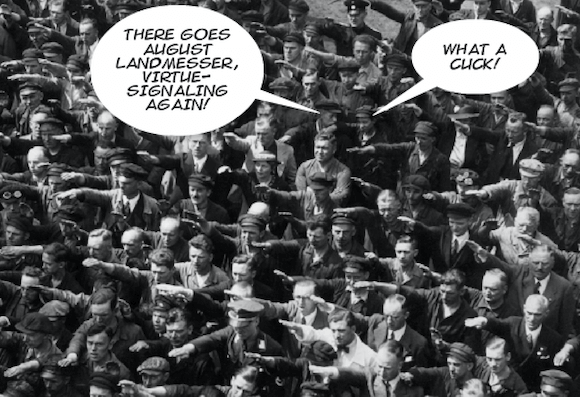

And if you fall out of line, we'll, you’re just a virtue-signaler. And we all know how bad virtue-signalers are.

So yeah. Tribalism can be very, very bad.

Whenever there is any kind of mass psychosis or bizarre behavior—whether it’s as serious as Germany succumbing to Nazi propaganda about the Jews, or Americans using violence to stop the lawful transfer of power, or it’s just a bunch of jerks mobbing someone on Twitter—people often ask: is this how people really are? Are the jerks in the mob on Twitter really such a-holes in real life? Were Germans who refused to do business with Jews in the 1930s and turned a blind eye to the atrocities of their government inherently evil, or just weak?

My answer tends to be: yes. Yes, the people are really like that, in both ways. They are really that bad, and they also have the potential not to be. Human nature is consistent, in that most people in any given situation will react the same way. But human nature is also very flexible, in that the behavior of humans depends greatly on their environment. Humans are inherently social creatures. The extent to which we are interdependent for our success and survival can hardly be overstated. And when some critical mass of people demonstrate their belief that it is OK to behave in a certain very bad way, and if they seem to be relatively anonymous and free from punishment, that critical mass can often determine how the rest of surrounding humanity behaves.

You can blame tribalism for this, but tribalism is not just the disease. It is also the cure.

Tribalism Can Be Good

Not too long ago I listened to two of my favorite podcasters have a discussion: Sam Harris and Russ Roberts. Roberts had previously appeared on Harris’s show, and now Harris was returning the favor. Their discussion was fascinating and wide-ranging and I recommend the whole thing to you, but the part that caught my attention was Russ Roberts’s praise for things like dogmas and tribalism. Harris starts out by positing that the dogmas people hold are divisive and the enemy of reason. Russ Roberts responded:

Russ Roberts: I'll defend it a little bit, and then I want to reflect on it: it was a very thoughtful outline of the challenge of dogmatism. I wrote an essay on--I don't know if you've ever seen the show Come From Away, the musical?

Sam Harris: No. No.

Russ Roberts: It's a beautiful show, ridiculously beautiful show. It's about on 9/11 U.S. airspace was closed and a bunch of flights had to land in the middle of nowhere in Canada. And, the show is about how the tiny group of people who lived there rose to the occasion. And, part of the reason they rose to the occasion is that they had a tribal urge--they had a certain image of themselves--as, I'd say, resilient. Among other things, of course. Some of them not so attractive probably. But, that resilience carried through and it--to say it saved the day is an understatement for the people who landed there.

And, similarly, in a religious community that's effective, it's divisive--dogma is divisive--for the people outside the community. It's incredibly unifying and exhilarating for the people inside the community. If you've not been part of that, it's hard to imagine. There are very few movies or treatments of it that have captured it.

It’s a different way of thinking about tribalism, isn’t it? It can indeed be unifying and can help motivate people to do great things in a crisis. There is no doubt that the good people of Ukraine are getting through the illegal, unjust, genocidal war that Vladimir Putin started, by pulling together and uniting behind the tribal cause of defending their country.

And that’s the thing I want to get across: it’s not tribalism per se that is the bad thing. It’s the way tribalism is used that matters. When tribes form and band together and act around laudable principles, they can do great things.

I recently finished an excellent book called The Volunteer, by Jack Fairweather. It is a history of Witold Pilecki, the Polish patriot who volunteered to go to Auschwitz, so he could tell the world what was going on there. Surely you’ve heard of Pilecki’s story, right? After all, a story like that is so great, it’s unthinkable that it would not be taught to every schoolchild.

Well, I got to the age of 54 before I heard about Pilecki. And I bet most of you have not heard of him either.

Above: Witold Pilecki

I won’t re-tell the whole story here. I encourage you to read it. But for present purposes, it’s important to note that when Pilecki first arrived at Auschwitz, the conditions of the camp had turned most inmates into people who were “cantankerous, mistrustful and in extreme cases even treacherous,” in the words of one prisoner. Inmates would denounce one another to the authorities for scraps of food, and turn in unidentified Jews to get out of work. None of this should surprise anyone who has read about extreme penal colonies or concentration camps; a book I read about the North Korean concentration camps said that inmates often view their own family members as competitors for food, and would readily betray those family members to get a decent meal. We can’t blame the inmates for this behavior. Again, this is how human nature typically responds in such situations. No movie would ever dare depict this for fear of being seen as blaming the victims. But this is how human nature is.

Unless, of course, a critical mass of people fights it. Pilecki saw his job as saving the weakest and bucking up the spirits of the people in Auschwitz. With his unparalleled courage and leadership skills, Pilecki saved countless lives and built an underground resistance organization numbering in the hundreds. All of a sudden there was a critical mass of people who had the spirit to resist. And it spread.

The resistance group was a tribe of its own.

Tribalism caused the Nazis to obey their orders to establish Auschwitz, to starve and beat and murder prisoners, and ultimately exterminate them in unthinkable numbers. But the resistance to that evil was a group effort too. Like Nazism, resistance was also a tribal phenomenon. It’s hard for resistance to happen any other way. It’s easy to talk a good game about independence and standing for principle. But it’s a lot easier when you have people standing with you.

We Need Expertise

Another dichotomy that comes to mind: as a general rule, we need to trust the experts.

But we also need to question the conventional wisdom. Sometimes, in the right way. I’ll discuss that, and the question of expertise, next—as well as many other interesting topics, for the paid subscribers.

If you haven’t taken that leap yet, I’ll summarize my conclusion briefly: life involves judgment calls. It’s tempting to place all your faith in principles like opposing tribalism, or sticking with the group no matter what, or seeking commentary that challenges you, or seeking commentary that reinforces your beliefs. But there is a time and place for all of our decisions, and they can’t always follow such simple rules. The only correct principle is to develop a world view about how you know when you are doing the right thing, and then try to do it. There is no easy shorthand for that.

If you find that conclusion unsatisfying, and you hated this newsletter, well . . . I warned you!

If you didn’t hate it, and you might like to read more along the same lines, come with me as we discuss the tension between the need for expertise and the desire to question conventional wisdom, and other philosophical dichotomies.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Constitutional Vanguard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.