What the New York Times Editorial on "Cancel Culture" Gets Right . . . and Wrong

More important is our Responsibility to Listen. Because if nobody listens to reason, reason loses its power.

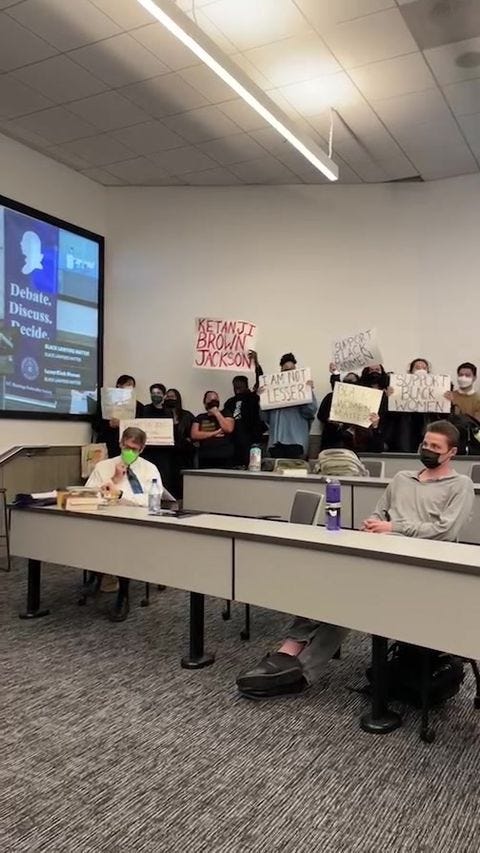

Above: do these Yale Law students disrupting a panel discussion on free speech deserve federal clerkships? At least one federal judge says no.

The concept of “cancel culture” is once again part of the national discussion, thanks to a New York Times editorial released yesterday on the topic.

However you define cancel culture, Americans know it exists and feel its burden. In a new national poll commissioned by Times Opinion and Siena College, only 34 percent of Americans said they believed that all Americans enjoyed freedom of speech completely. The poll found that 84 percent of adults said it is a “very serious” or “somewhat serious” problem that some Americans do not speak freely in everyday situations because of fear of retaliation or harsh criticism.

This poll and other recent surveys from the Pew Research Center and the Knight Foundation reveal a crisis of confidence around one of America’s most basic values. Freedom of speech and expression is vital to human beings’ search for truth and knowledge about our world. A society that values freedom of speech can benefit from the full diversity of its people and their ideas. At the individual level, human beings cannot flourish without the confidence to take risks, pursue ideas and express thoughts that others might reject.

Most important, freedom of speech is the bedrock of democratic self-government. If people feel free to express their views in their communities, the democratic process can respond to and resolve competing ideas. Ideas that go unchallenged by opposing views risk becoming weak and brittle rather than being strengthened by tough scrutiny. When speech is stifled or when dissenters are shut out of public discourse, a society also loses its ability to resolve conflict, and it faces the risk of political violence.

I agree with the spirit of some of what the editorial expresses. Freedom to express views is indeed important — and though we typically worry about government interference with freedom of speech, a culture of free speech is important as well.

It would be very easy, therefore, to write a rah-rah newsletter cheering the New York Times editorial, noting that “cancel culture” certainly does exist, pointing out a few egregious examples (and they certainly exist), and collecting some clicks and attaboys from the whole thing. In fact, I’ll do some of that in a moment.

But leaving the matter there would be boring.

I’d rather acknowledge the good in the editorial, and criticize the bad in it. But more importantly, I then want to take us beyond the admittedly important issue of freedom of speech to what I call the Responsibility to Listen. Because without it, freedom of speech means little.

The Good in the Editorial

I’m happy to see editors of the New York Times acknowledge the existence of “cancel culture,” because it’s a glaring problem at their own newspaper. Remember: this is a newspaper that fired a good health reporter for doing nothing but mentioning the N-word in an innocent and non-racist context. Similarly, throughout the country, our culture has too often become hostile to, not just the expression of controversial views, but also the expression of even innocent views that might arguably intersect, however tangentially, with controversial topics. The deniers are out there, of course:

But the deniers are wrong. I have written about this before, and although there are many examples, three leap to mind:

The professor who stepped back from teaching a seminar on Verdi operas after being reprimanded for showing his music students Laurence Olivier’s Otello.

The San Francisco art museum curator who resigned because he “ended a presentation about new acquisitions by artists of color by saying, ‘Don’t worry, we will definitely still continue to collect white artists.’”

The USC business communications professor who was suspended for teaching students about a very widely used “filler word” in Chinese that happens to sound like a racial slur.

Nowhere is this hostility more pronounced than in the context of race, and it is no coincidence that race underlies most of the examples of “cancel culture” that stun people of good will and common sense.

The Nonsense in the Editorial

Unfortunately, much of the good in the editorial is mushed together with silly nonsense. The very first sentence of the thing is garbage:

For all the tolerance and enlightenment that modern society claims, Americans are losing hold of a fundamental right as citizens of a free country: the right to speak their minds and voice their opinions in public without fear of being shamed or shunned.

Wrong. While Americans have a right to speak, they don’t have a right to say shameful things without having people point out how shameful those things are. I have made the point many times that shaming and shunning is itself a form of speech, and the propriety of shaming and shunning is a matter of line-drawing. For instance, few people in America deserve shaming and shunning as much as Tucker Carlson. Carlson spent months questioning the efficacy of vaccines with sinister half-truths. Now, he spews a steady stream of pro-Putin propaganda so reliably submissive to the Kremlin narrative that his shameful monologues are routinely featured on Russian state television. Carlson has a constitutional right to say most of the stupid and evil things he says, but he has no right to say them without harsh criticism — which is, after all, a form of free speech as well.

The editorial makes this mistake throughout. The entire editorial is centered around a poll that asks questions about “retaliation or harsh criticism” — as if the two concepts are equivalent. Pollsters asked respondents if they held their tongues due to fear of “retaliation or harsh criticism.” Had they engaged in it themselves? How much of a problem is it that people are scared to speak because they fear “retaliation or harsh criticism”?

But criticism, including harsh criticism, is central to American political debate. I believe it is nearly impossible to engage in serious political discussion without it. As an illustration: for Lent, as I have done in some previous years, I have given up criticism, complaining, and chips: the Three Cs. Now, giving up chips is easier, because eating chips is less of a reflex action than the first two. (Although I did bring home a bag of Ghost Pepper potato chips from Trader Joe’s the other day, and had constructed in my mind a meal wherein I breaded some cod fillets with crumbled potato chips . . . and actually started to open the bag before I remembered my Lenten sacrifice.) A pledge to give up criticism and complaining, by contrast, is more of a pledge to Be On The Lookout for your statements that might constitute criticism and/or complaining, and to recruit confederates to aid you in this effort — a role my wife plays with alacrity. “That sounds like complaining!” is her favorite phrase these days, and I thank her for her remarkably enthusiastic help. But, as in years past, I have given myself a Special Dispensation to criticize and perhaps even complain in my political writing — because without those tools, I’m not sure I’d have anything to write about. I have asked myself, however, to be sparing and careful in the use of those tools, and to make a real effort not to use them in a gratuitous or mean manner.

So yeah, one needs to be able to criticize ideas, and sometimes even people, to engage in political debate. That criticism will sometimes be harsh — and sometimes it needs to be.

Lack of Free Speech Is Not Our Biggest Problem — Lack of *Listening* Is

I think the current debates over “cancel culture” — including the arguments in the New York Times editorial — miss the point to some degree. Yes, people are feeling nervous about uttering some obvious truths, and about even touching on certain hot-button topics. This is, to some extent, a concern about there not being enough freedom to speak. But I think it is also useful to think of nearly any controversial story about “free speech” or “cancel culture” as a failure of the listener rather than a suppression of the ideas of the speaker. In short, I argue that we have what I call a Responsibility to Listen.

Don’t misunderstand me. I don’t say that I have a responsibility to listen to any crackpot who wants to speak to me. I’m certainly not going to waste my time thoughtfully stroking my beard as I carefully consider the arguments of @Groyper1488 that white supremacist Nick Fuentes is a misunderstood genius.

What I am saying is that, in a context where we acknowledge that communication is important, the listener has a responsibility as great as that of the speaker: a responsibility to be charitable and fair to the speaker, to give the speaker a chance to make his or her case, and to respond with honest arguments rather than trollish behavior. I am talking about contexts such as a political debate, or a speech by a speaker at a university, or a jury trial.

As a trial lawyer, I have often said that it is pointless to try to persuade someone who is determined not to be persuaded. This is why jury selection is so important. Indeed, many lawyers in our office say that “cases are won and lost in jury selection.” As prosecutors, we come into the courtroom confident that we have a case that we can prove beyond a reasonable doubt. But if we get even one juror who is bound and determined to acquit the defendant regardless of the evidence, due to their own personal biases, we are going to lose. My preferred course of action is not to try to persuade such people, because in the end they will almost never come around, no matter how strong my position is. I’d rather exercise a peremptory challenge (or, better yet, a cost-free cause challenge) to get them off my jury.

Similarly, in politics, we all know people who believe the craziest things, and are impervious to evidence. If it serves the interests of their tribe to believe that Putin is truly trying to get rid of the Nazis in Ukraine, or Joe Biden stole the election from Trump, or vaccines implant microchips in our bodies, they will believe it.

But sometimes we can’t just shrug our shoulders and block them or excuse them from the court of public opinion. To take one obvious example: some of these people are our relatives who might die if they don’t get a vaccine.

Some of these people are just stupid and/or pigheaded. But many are actually educated. Their problem is that they don’t listen. They hear, but they do not really listen. When an argument that contradicts their priors comes across the transom, they immediately run to their tribe’s most reliable Web sites to find the data to refute the argument. They do not listen and consider for a moment that perhaps the argument is true.

This is how perhaps half the Russian public believes that Putin is not really at war in Ukraine and that his limited military operation is truly an act of defense. Yes, information is more difficult to come by in Russia, but it’s accessible if people want to seek it out. The fact that a sizable majority of Republicans believe Joe Biden stole the 2020 election shows that groupthink works in free societies too. These Republicans have access to the truthful information about the 2020 election. They just choose not to listen.

They have a Responsibility to Listen and they are not undertaking that critical responsibility. But without a real, genuine attempt to listen on the part of the audience, free speech is worthless. It will persuade nobody.

I think it’s useful to look at some recent free-speech/cancellation issues through the lens of the Responsibility to Listen.

Shouted Down at Yale Law School and UC Hastings

One of the more shameful speech-related incidents of the past few weeks occurred at Yale Law School, at a panel hosted by the Federalist Society. The National Review explains the purpose of the panel: “The Yale panel in question was designed to show that speakers from different political and cultural positions could both support free speech. The panel’s speakers were Monica Miller, the legal director of the American Humanist Association, and Kristen Waggoner, the general counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom.” But students disrupted the panel, as reported here by the Washington Free Beacon:

More than 100 students at Yale Law School attempted to shout down a bipartisan panel on civil liberties, intimidating attendees and causing so much chaos that police were eventually called to escort panelists out of the building.

. . . .

When a professor at the law school, Kate Stith, began to introduce Waggoner, the protesters, who outnumbered the audience members, rose in unison, holding signs that attacked ADF. . . . As they stood up, the protesters began to antagonize members of the Federalist Society, forcing Stith to pause her remarks. One protester told a member of the conservative group she would "literally fight you, bitch," according to audio and video obtained by the Washington Free Beacon.

The protesters claimed that their protest was “free speech” (it wasn’t) and were asked to leave. They did, but continued to impede the ability of those inside to continue the discussion:

The protesters proceeded to exit the event—one of them yelled "Fuck you, FedSoc" on his way out—but congregated in the hall just outside. Then they began to stomp, shout, clap, sing, and pound the walls, making it difficult to hear the panel. Chants of "protect trans kids" and "shame, shame" reverberated throughout the law school. The din was so loud that it disrupted nearby classes, exams, and faculty meetings, according to students and a professor who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

. . . .

At times, things seemed in danger of getting physical. The protesters were blocking the only exit from the event, and two members of the Federalist Society said they were grabbed and jostled as they attempted to leave.

"It was disturbing to witness law students whipped into a mindless frenzy," Waggoner said. "I did not feel it was safe to get out of the room without security."

As the panel concluded, police officers arrived to escort Waggoner and Miller out of the building.

Here is video of the Yale students protesting:

A similar shout-down happened to Ilya Shapiro at UC Hastings on March 1. Here is a long video of that outrageous disruption:

And here is a shorter one:

I am not the only one outraged by this behavior. As David Lat reported, at least one federal judge wrote his colleagues to opine that the offending students should be identified and blacklisted from getting prestigious federal clerkships:

The latest events at Yale Law School, in which students attempted to shout down speakers participating in a panel discussion on free speech, prompt me to suggest that students who are identified as those willing to disrupt any such panel discussion should be noted. All federal judges—and all federal judges are presumably committed to free speech—should carefully consider whether any student so identified should be disqualified from potential clerkships.

Is that a horrific “retaliation” for free speech that exemplifies the worst of “cancel culture”? I don’t think so. If I were a federal judge, I would not want any of these spoiled brats working for me. I think they should be identified and suffer the consequences of their illiberal behavior.

But what I want to focus on is the failure to listen. The fact that the Shapiro event at Hastings was utterly canceled, and that (according to Lat) the event at Yale Law School was”significantly disrupted,” meant that, to varying extents, the speakers were not allowed to speak; that is true. But at least as significant — and probably more, in my view — is the fact that the students refused to listen.

If that doesn’t sound right to you, imagine this hypothetical: pretend that all of the students you saw in these videos sat politely, with the intention of asking challenging questions in a respectful tone after the prepared remarks, but the speaker was struck with a coughing fit and unable to deliver any remarks at all. The speaker would have not been able to deliver his speech, but the students would have been willing to listen. I think we would find that less offensive than what actually happened.

You might find that hypothetical off the mark, because the disruption is really what offends you. So forget the disruption and imagine that the audience sat there politely, but deliberately did not listen to a word the speaker said. Instead, they all reported afterwards that they had deliberately chosen, as a group, to mentally check out of the event as a form of protest, and instead spent the time trying to memorize the latest poem by National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman. Would that be any different than the speaker being unable to speak at all?

If a speaker speaks in a forest, or a university classroom, and nobody listens, has the speaker made a noise? I don’t know the answer to that, but I know he or she has not communicated anything.

The Other NYT Cancel-Culture Piece

In addition to yesterday’s editorial, the Times published another controversial op-ed recently that demonstrated how pervasive the culture of non-listening is:

In the classroom, backlash for unpopular opinions is so commonplace that many students have stopped voicing them, sometimes fearing lower grades if they don’t censor themselves. According to a 2021 survey administered by College Pulse of over 37,000 students at 159 colleges, 80 percent of students self-censor at least some of the time. Forty-eight percent of undergraduate students described themselves as “somewhat uncomfortable” or “very uncomfortable” with expressing their views on a controversial topic in the classroom. At U.Va., 57 percent of those surveyed feel that way.

When a class discussion goes poorly for me, I can tell. During a feminist theory class in my sophomore year, I said that non-Indian women can criticize suttee, a historical practice of ritual suicide by Indian widows. This idea seems acceptable for academic discussion, but to many of my classmates, it was objectionable.

The room felt tense. I saw people shift in their seats. Someone got angry, and then everyone seemed to get angry. After the professor tried to move the discussion along, I still felt uneasy. I became a little less likely to speak up again and a little less trusting of my own thoughts.

I was shaken, but also determined to not silence myself. Still, the disdain of my fellow students stuck with me. I was a welcome member of the group — and then I wasn’t.

Here again, the real issue is not the inability to speak, but a failure to listen. Think about the ideals I mentioned above as core to the Responsibility to Listen. Are the other students being charitable and fair to the speaker? No. Are they giving the speaker a chance to make her case? Not really. Are they responding with honest arguments? No; they are simply venting anger. Someone who decides not to be “silenced” can still speak, but what does that really matter if nobody listens?

Listening Is As Important As Speaking — and Maybe *More* Important

Communication is a two-way street. You can read these words but not absorb them. You can hear a speaker but not listen. But if “freedom of speech” is an important right, both in the law and in our culture, then our Responsibility to Listen is an important responsibility that goes hand in hand with the speech right.

What can we do about it? The same things we can do to promote freedom of speech in our culture. Every one of us is responsible for building that culture. You can start, today. Right now.

And when you hear about the next “cancel culture” debate — it won’t take long, I promise you — ask yourself: is the main problem here an inability to speak? Or is it an unwillingness to listen? You might be surprised once you start applying this lens to all of these controversies. And hopefully it will help you listen better yourself, and help develop a culture of listening that can give real meaning to our cherished right of free speech.

Good essay, but one point of disagreement:

The protestors who disrupted the Yale panel discussion were loathsome, but their main crime was actively blocking speech, not in failing to listen. After all, many audience members wanted to actually hear the discussion that the protestors silenced. The protestors thereby quashed the rights of both speakers and listeners. Furthermore, the protestors inhibited the formation of future panels that might have, little by little, chipped away at the excesses of the current orthodoxy. Even an audience that passively "tuned out" the speech would not have had the same chilling effect.