What I Would Have Told House Managers: Don't Ever Stipulate to Your Most Powerful Evidence

It's Prosecution 101

Above: Rep. Jamie Raskin decides a sing-song reading of a written statement would be more effective than hearing that statement from the witness herself.

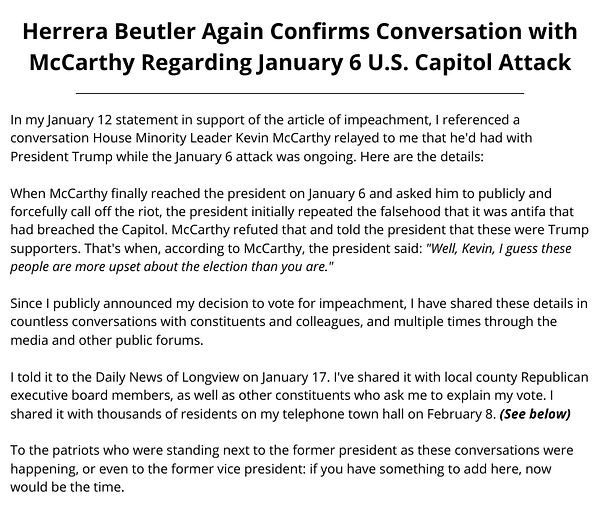

Yesterday, for a brief and shining moment, it looked like we were going to hear from Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler in the second impeachment trial of former president Trump. Here is the essence of what she would have testified to:

But it was not to be. Democrats caved and read her statement into the record, allowing a quick acquittal vote so senators could leave town for Valentine’s Day. Priorities!

Today, the House managers are trying to justify this disastrous decision. As a prosecutor who has tried plenty of cases, I’m here to say: there is no justification for this. I’ll tell you why in this missive — and I’ll tell you a story about a hypothetical gang murder case, loosely based on my experience, to vividly explain why live testimony is better than stipulations.

First, here’s Rep. Raskin offering his excuse for not calling Rep. Herrera Beutler as a witness:

You know what, I mean, I don’t want to . . . We tried this case as aggressively as we could on the law and on the facts. We did everything that we could. We got from the president's lawyers exactly what we wanted which was the entering into the evidentiary record of the statement by our colleague Congresswoman Beutler. And we got that. I was able to read it before the entire country and it became part of the case. And it became an important part of our case.

If, again, you know, we could have had 500 witnesses and it would not have overcome the kinds of arguments being made by Mitch McConnell and other Republicans who were hanging their hats on the claim that it was somehow unconstitutional to try a former president or that the First Amendment somehow gave him a right to incite violent insurrection against the union.

He went on to argue that Trump’s lawyers were threatening to call Nancy Pelosi and “we were not going to allow them to turn it into a farce.” But the only way it would have turned into a farce is if one or more Democrats had voted that Pelosi was a relevant witness. The same way that Republicans controlled whether evidence would be presented at the first impeachment trial, Democrats controlled it this time — in large part thanks to Trump’s suppression of the vote in the runoff elections in Georgia by spending his rallies bitching about non-existent election fraud.

Delegate and House manager Stacey Plaskett also tried to justify the decision in similar fashion:

"I know that people are feeling a lot of angst and believe that maybe if we had (a witness) the senators would have done what we wanted, but, listen, we didn't need more witnesses, we needed more senators with spines," Plaskett, who represents the US Virgin Islands' at-large congressional district and served as one of nine impeachment managers, told CNN's Jake Tapper on "State of the Union."

. . . .

"I think we wanted to get in what we wanted and we did. We believed that we proved the case. We proved the elements of an article of impeachment," she said. "It's clear that these (senators) were hardened -- that they did not want to let the President be convicted or disqualified."

There are basically two arguments being made here: 1) the House managers would not have won anyway, so why bother? and 2) hey, we got the evidence in anyway, so what’s the harm?

The first argument is easily disposed of. The impeachment managers knew they were going to lose all along, so why bother putting on a trial at all? Obviously, House managers were not persuaded by that argument, nor should they have been. Other than failing to call witnesses, they put on an excellent presentation. They had videos that showed the effect of Trump’s words on the crowd. They presented evidence of Trump’s lies, of his inaction during the riot, and of his involvement in setting up the entire event, including becoming involved in changing the date of a permit for a rally to January 6, rather than after the inauguration when the rally had originally been scheduled. The evidence truly was well put together.

Why go to all that trouble if you knew you were going to lose anyway? For several reasons. The impeachment was not just about disqualifying Trump. In a very real sense, the Republican party was on trial. The trial was about showing the complicity of the Republican party in sticking with Trump despite the gravity of the evidence being presented. The stronger the evidence, the more obvious that complicity was. For the Democrats, the goal would be to weaken the Republican party; for classical liberals like myself, the goal would be to weaken the grip of the cult leader on the cult, and to move the party to some semblance of sanity. No matter the goal, it could be best accomplished with the strongest evidence.

Which leads me to argument number two: “hey, we got in the evidence anyway.” The prosecutor in me says: the hell you did. To explain why, I think I need to take a step back and give you a window into my experience as a prosecutor. (As always, what I say here, I say in my private capacity and not on behalf of my office.)

NEVER STIPULATE TO THE CORONER

I tried murder cases for over ten years, and have convicted dozens of defendants of murder. One thing I have learned during that time: you don’t stipulate to your most powerful evidence.

For example, it is relatively common in a criminal trial for a defense lawyer to ask: “Hey, will you stipulate to the coroner? It’s not like we’re disputing that this guy was killed by gunshot wounds.”

The answer to that question is always a hard “no.”

The reason is simple: autopsy evidence is always more effective when presented live, rather than reading in a cold stipulation that both sides agree the victim was killed by gunshot wounds.

I think most prosecutors overlook the value of a coroner’s testimony. (In Los Angeles, these doctors with special training in forensic pathology are known as “Deputy Medical Examiners” who work for the Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner, but I will call them “coroners” in this missive just to keep it simple.) To my way of thinking, a coroner’s testimony can often be one of the most central pieces of evidence in a murder case. You have to read the report cover to cover several times, and familiarize yourself with any anatomical or medical terms that are unfamiliar. You need to speak to the coroner in advance and go over each gunshot wound in detail (for most gang murders are gun murders), and confirm that the coroner agrees that any hypothetical scenario you might present to him or her is consistent with the evidence.

Let me give you a hypothetical case that is not based on any of my cases, to avoid any complications that could arise from my speaking about a particular case — not the least of which is that a victim’s family member could stumble across my missive and recognize the case, re-opening psychological wounds. Although this is a purely made-up case, the concepts I will be discussing in my hypothetical case will be based on all my experience.

THE STORY OF A LONG BEACH GANG MURDER

In our story, the defendant is an East Side Longos gang member from Long Beach, who has murdered a rival gang member from the Insanes, a primarily black gang also located in Long Beach. A car full of East Side Longos was driving down the street when it passed the Insane gang member, who recognized the occupants of the car as his rivals. According to witnesses, including a fellow Insane gang member walking with the victim, as well as three bystanders, the Insane held up his thumb (a typical Insane gang sign) while shouting at the car: “This is Insane!” The car screeched to a halt and a back passenger jumped out and fired three shots at the fleeing and ducking Insane gang member, striking him twice in the back. The victim fell to his knees, and the defendant ran up behind him, firing two more shots at close range into the kneeling victim’s back, at which point the victim fell forward onto the front lawn of a residence. The defendant then held his gun against the base of the back of the victim’s head, fired a fifth shot, and hopped back into the car, which drove away.

The car was stopped a quarter mile away with the defendant still in the back passenger seat. Police saw a firearm thrown out of the back passenger window before the car stopped. The gun was recovered and while no prints were lifted from it, a DNA swab of the gun showed a mixture of three people, with the defendant being a potential contributor to the mixture. Due to the partial nature of the profile, the random match probability was only about 1 in 3000. But your best piece of evidence was found on the defendant’s shirt: droplets of blood containing DNA matching the victim. As the case comes up for trial, you’re feeling pretty good about it. (Indeed, you know this story is made up because none of my cases were ever this good.)

Except that the rest of the case is not playing out in as straightforward a manner as it seemed to on paper. First of all, the companion of the victim is brought to court in a blue L.A. County Jail jumpsuit. Weeks after the murder happened, he was arrested, convicted, and sentenced for an unrelated robbery, and he is now very hostile to you. The reason for this is obvious: not only is he upset about his conviction, but your detective also says that the word on the street is that before he went into protective custody, he was beaten by fellow inmates for being a “snitch.” When you ask him questions on the stand, he just stares at you and says nothing. The court holds him in contempt — a toothless action because the five-day sanction means nothing to a man who has recently been sentenced to twelve years in prison. Your questions are stricken from the record, since no answers were provided.

Fortunately, you called him at the preliminary hearing, before his robbery arrest, so you can read in his testimony at the trial. But at the preliminary hearing, he recanted his identification of the defendant (a common occurrence in gang cases), claiming he had been on drugs when the shooting went down, and that he just told the officers what they wanted to hear in their initial interview with him because they had threatened him. The recording of that interview, which you played at the preliminary hearing (even though the judge gave you a hard time about it), shows the witness’s preliminary hearing recantation to be an obvious lie. In that interview, the witness is crying and saying he is going to stand up for his dead friend, and that he recognized the shooter from two previous incidents — but he doesn’t want to have to testify in court, and if they call him to the stand, he’ll deny everything. Thank goodness the police recorded the statement; it is very convincing. Still, the jury never gets to see this witness live, and could not evaluate his demeanor at the previous hearing when he recanted.

As for your three bystander witnesses, one has moved back to Mexico. He knew the shooter from the streets and identified him in an interview without hesitation. He was the strongest ID witness you had. But the witness’s brother has told your investigating officer that some Insanes came by their house three days before the preliminary hearing and there was a confrontation outside. The Insanes had beaten the witness and threatened to kill him if he went to the preliminary hearing. Still bleeding profusely from his head, the witness immediately packed his things and headed for Mexico. The witness’s brother won’t tell you where the witness went in Mexico, and you can’t find him. So much for that witness. The jury will never hear a thing about him.

Your second bystander witness is a sleepy-eyed white guy who always seems like he just took a few hits of weed. He testified at the preliminary hearing and stuck to his story, but at the end of the second day of insulting and endless cross-examination at trial, the defense attorney has him robotically answering “yes” to literally any “isn’t it true” question that the defense attorney asks. “Isn’t it true the shooter had no tattoos on his arms?” “Yes.” (Your objection that the witness previously said the shooter had on a long-sleeved shirt is overruled.) “Isn’t it true my client has tattoos on his arms?” “Yes.” “So my client is not the shooter, isn’t that true?” “Yes.” The defense attorney’s last question is: “In fact, sir, you weren’t even there, isn’t that true?” The witness answers: “yes.”

You get up on redirect and ask: “Sir, were you at the shooting or not?” He answers that he was, in a tone that conveys “of course I was!” You ask why he just told the defense attorney that he hadn’t been present. He sighs and says: “Did I say that? I don’t know, man. I just wanted him to stop asking me questions.” He reconfirms that the shooter had on a long-sleeved shirt and that the defendant is the shooter, but the damage has been done. It sounds to the jury like this guy will say anything.

Your third witness was threatened after the preliminary hearing and was later found shot dead on the street. There were no witnesses. The case is still being investigated. The word on the street is that the Insanes killed him for testifying, but nobody can prove anything. You’re able to read in his preliminary hearing testimony.

So far, you have sleepy-eyed weed guy who will say anything, and two witnesses that you’re having to read in through a transcript. Now it’s time to put on your coroner.

You could present the coroner’s testimony in such a case by reading a sing-song stipulation into the record that says something like this: “The parties stipulate that a qualified medical examiner conducted an autopsy of David Washington on January 12, 2019, and that if called to testify, the deputy medical examiner would testify that the victim died of five gunshot wounds, all of which were fatal.” The court would advise the jury that they must accept this as fact, and you move on to your next witness. Done! To paraphrase Rep. Raskin, you got from the defense lawyers “exactly what you wanted”; namely, a statement read into the record that the victim died of gunshot wounds. Yay!

Instead, you put on the coroner. You show photos of the dead victim’s body, taking care to obscure his genitalia with black rectangles for the sake of decency and his privacy. You go over each of the gunshot wounds in detail. In the photos, the body has been cleaned; at the scene there was blood everywhere, but these pictures show round holes for entrance wounds and somewhat less round holes for the two exit wounds. (Three deformed projectiles were recovered from the body at autopsy.) Under your questioning, the coroner traces the path of each bullet, including all organs that were penetrated. The jury learns that two of the wounds to the back have a slightly upward angle, and the coroner agrees with you that such wounds could be caused by the bullets entering the back while the victim is ducking and running away. It turns out that’s what your witnesses were saying happened during the initial gunshots.

Two of the other back wounds are in a different area of the back, with the entry wounds higher up, but the path of the wounds going back to front at a distinctly downward angle. The trajectory of these two wounds is very similar: both bullets traveled through the skin, the upper lobe of the lung, the heart, and came to rest near the ribcage. The wounds are surrounded by punctate abrasions that the coroner calls “stippling,” which is associated with the gun being fired from an intermediate range: approximately six inches at the lower end of the range, to roughly two feet at the upper end of the range. The coroner agrees that these wounds are consistent with a gunman standing over a victim kneeling on the ground and firing two shots into the victim’s back in rapid succession from about a foot away. The gun being pointed downward explains the downward angle of the wound trajectory; the similar path of the bullets corroborates the theory that they were fired in rapid succession; and the stippling corroborates the range. It turns out that’s what your witnesses were saying happened when the defendant shot the victim while he was kneeling.

The wound to the back of the victim’s head shows soot, which the coroner says is characteristic of a contact wound. He also says he is aware of cases where a gunman firing such a gunshot has had the victim’s blood blow back onto the gunman’s body. This corroborates your witnesses’s statements about the final gunshot, and explains how the victim’s blood could have gotten on the defendant’s shirt.

By calling the coroner, you were able to effectively corroborate the testimony of your witnesses, all of whom were initially interviewed and gave statements before the autopsy. They couldn’t have known that the coroner’s findings would back up their statements in every detail. This corroboration helps prove your witnesses’s testimony was accurate. What’s more, you would not have been able to elicit any of this in a stipulation. No defense attorney would agree to such a level of detail. Nor would the jury have been presented with effective and detailed testimony about the absolute devastation wrought by these bullets.

NEVER STIPULATE TO A REPUBLICAN CONGRESSWOMAN’S TESTIMONY DESCRIBING TRUMP’S CALLOUSNESS

These lessons apply to the impeachment trial. Rep. Raskin’s live testimony would have been far more effective than simply having it read in by a House manager. Don’t take my word for it. Look for yourself. Here is Rep. Raskin’s sing-song reading of the statement from Rep. Herrera Beutler:

Compare that to the statement Rep. Herrera Beutler gave when she cast her impeachment vote. She wasn’t telling her full story here, and she sounds a little rushed because she has a lot to say in a short time. (I understand Democrats refused to give Republicans voting for impeachment extra time to make their case. Brilliant!) Still, her direct statement is so much more effective than Rep. Raskin’s sing-song reading, it’s infuriating to think how compelling her testimony might have been at the impeachment trial.

There’s a reason former president Trump was reportedly happy that no witnesses were called. It’s not because he thought the statement being read into the record was the most effective way to handle this. Quite simply, the managers allowed themselves to be played.

By the way, the failure to call witnesses extends beyond Herrera Beutler. There was no excuse for House managers’ decision not to call Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to testify about how Trump had pressured him to “find” enough votes to swing the Georgia election. I can see a justification for not calling witnesses sympathetic to Trump, like Mark Meadows or Kevin McCarthy, who would likely have twisted the facts or even lied to protect Trump. But Raffensperger has been brutally honest throughout the election process, making clear that he had wanted Trump to win and had voted for him . . . but not minimizing Trump’s behavior in the least. He would have been a fantastic witness, and it is an outrage that impeachment managers failed to call him to testify.

My disappointment with the Democrats’ handling of the case does not end with their failure to call witnesses. Why on earth did they not ask Jaime Herrera Beutler or Adam Kinsinger — or better yet, both! — to be a part of the team presenting the case? These folks have pulled no punches about their views of Trump’s behavior, and I think it quite likely that they would have agreed to participate had they been asked to. That would have made the prosecution of the case truly bipartisan, as the vote to impeach had been. Was it really so important to give a starring role to Eric [expletive deleted]ing Swalwell instead?

Democrats, take it from a prosecutor: y’all could have done a hell of a lot better. No, Republicans probably would not have voted to convict in greater numbers. But you can control only that which is within your control — and while obtaining a conviction was not in your control, presenting the most effective case was. You presented a good case, but not the best you could have presented.

What a shame.

P.S. If you enjoyed this, feel free to forward it. By the way: my newsletter this week was going to be about the ways that a desire for “equity” can kill people, but this topic seemed more urgent. I think I’ll save that one for the paid subscribers on Wednesday. You can become one yourself by subscribing here:

The jurors for this trial were the Senators -- virtually all of whom had already made up their minds based on politics, not evidence. But Americans were the audience and we needed to hear the best, most complete case of what happened. We didn't get that.

I think you're entirely correct in your point and your hypothetical was entertaining to read.

But I think for Dems the decision was different. They knew they couldn't win. The GOP knew what had happened and had made their decision. Additional evidence wasn't going to change enough minds to get a conviction.

You rightly ask why start the trial at all since that was known from the beginning. I think the answer is that they wanted to make it clear to the US public what had happened. They were balancing that against the political costs from the GOP. Once the GOP made it clear they would go to war over witnesses the Dem's backed down.

https://www.kcrg.com/2021/02/13/joni-ernst-to-ny-times-reporter-on-impeachment-trial-total-total-s-show/