Above: the screenshot critics of the Adam Toledo shooting tend to ignore.

There’s a lot of misinformation out there about the shooting of Adam Toledo in Chicago earlier this year. So why don’t we start with the facts?

First: the bodycam video. You can start it at 1:45, where the officer puts his car in park and gets out. Once you have seen the single gunshot, things get tough to watch. Toledo is dying, and his agony is palpable and unforgettable. If stuff like that disturbs you, I’d skip it. But even so, make sure you fast forward to 5:35, when the officer shines his flashlight on the gun that Toledo ditched.

If you’re truly interested in learning the facts, the best thing you can do is watch the Chicago Police Department’s informative video on the incident, with footage of the original shooting that prompted the call, and different angles of the events leading up to the shooting of Toledo. You can watch it here. It’s just two minutes and 13 seconds long. I’ll use some stills from it in this newsletter.

At 1:27, the video freezes on the moment that you can see a firearm in Toledo’s right hand. There is a close-up on the left.

The video also provides the precise amount of time that has elapsed in the bodycam footage at the moment that you can see the firearm in Toledo’s right hand: 2 minutes, 3 seconds, and 343 milliseconds:

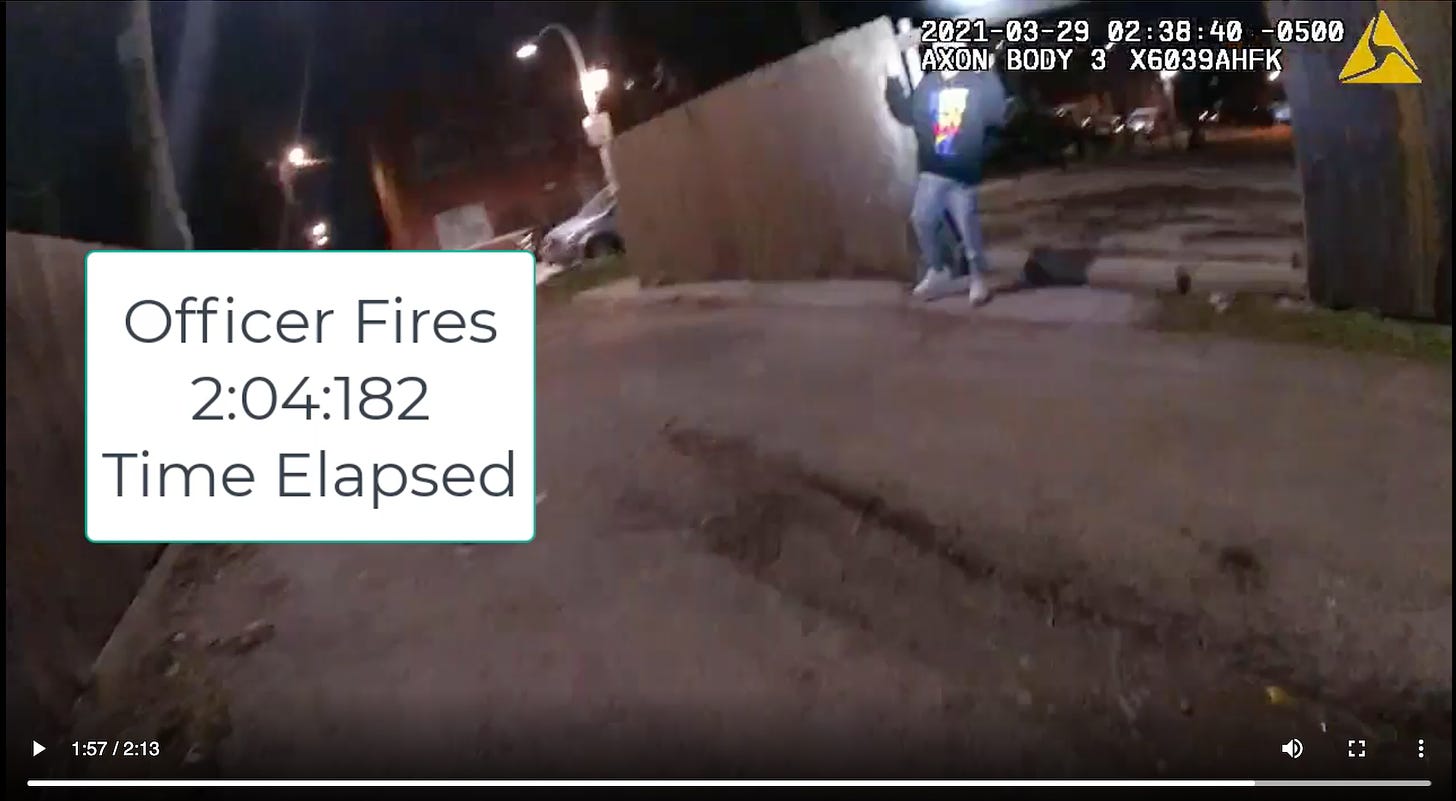

The video also shows the precise moment of the shooting, with the famous “look at his empty hands!” screenshot that all of our police-hating friends are posting on Twitter. The elapsed time on the bodycam footage: 2 minutes, 4 seconds, and 182 milliseconds:

When I subtract 2:03:343 from 2:04:182, I get 839 milliseconds between the two events. CPD gets 838:

It’s not necessarily the case that they are bad at math; they might be measuring fractions of milliseconds. Either way, we are talking barely over .8 seconds total.

Try this experiment: grab a phone and open a stopwatch app. Hit “start” and think to yourself — as fast as you possibly can, but without speaking out loud — the words “oh shit he’s got a gun I’d better fire” . . . and then stop the stopwatch. Do it several times. When I did it, I tended to get between .75 seconds and around a second or so. Racing my mind as fast as I can, I can’t even think those words much faster than 839 milliseconds.

The people opining about this on Twitter appear to have absolutely no concept of a thing often called “perception-reaction time”: the time between perceiving a need for action and the time it takes to take the action. I’m not an expert on this topic, which comes up a lot in auto accident reconstruction cases, and Web research does not reveal any completely consistent standard length of time between perceptions and reactions. Unsurprisingly, perception-reaction time can depend on a number of factors, like whether the event is expected, distractions, visibility, cognitive impairment, and the like. This discussion, which seems to be but one of many available, seems to suggest a widespread consensus that the average time between perception and reaction is slightly over a second, but it can certainly be quicker or longer than that. The point is: it’s not instantaneous. There’s a reason you’re advised to leave a fair amount of distance between you and the vehicle in front of you on the freeway; namely, it will take you a certain amount of time to perceive that the car in front of you is slowing or has illuminated its brake lights. Then you will have to react to that perception and hit the brake with your foot. All of this takes time.

People on Twitter keep telling me that cops should somehow surmount these obstacles presented by human physiology, by virtue of their training. “We hold cops to a higher standard, because they are trained, so they cannot use reaction time as an excuse” is a good summary of what many tell me. But this is nonsense. Cops are not superhuman, and training cannot give you superhuman reflexes.

Thinking about this shooting in a common-sense fashion, then, taking perception-reaction time into account, it’s relatively easy to see how a cop could end up shooting someone who ends up having nothing in his hand:

The cop seems a gun in the suspect’s right hand

The suspect then tosses the gun behind a fence, but his body and the fence block the fact that he is discarding the gun

The suspect then whirls around and shows his hands

The cop shoots him

It probably took you a few seconds to read those four bullet points, but the actual action happened in less than a second. If you say the classic ONE-Mississippi, the suspect has a gun in his hand when you say ONE and has whirled around before you finish the word “Mississippi.” My guess is, the cop saw the gun and saw the kid whirl around and that was all it took. The cop decided to shoot.

Was it a mistake? Of course it was. Ultimately, the cop shot an unarmed kid. That’s a mistake any way you slice it. But is it a mistake that is understandable, or one that should be criminal?

One could argue that the cop should absolutely wait to see the kid’s hands before shooting. That is arguably the correct view . . . but following this advice could also easily cost a police officer his life. Then again, the police officer’s decision not to wait cost Adam Toledo his life.

It’s a very tough situation. But who was responsible for placing the officer in this nearly impossible predicament?

Adam Toledo was.

He is the one who was running from a cop during early morning hours; who kept running after being told to stop; and who then suddenly whirled around after ditching the gun. (It seems clear to me that Toledo had no idea he was in great danger of being shot, and was instead far more concerned with ditching the gun and then showing his empty hands as quickly as he could — the old “who, me, with a gun? So where did it go?” criminal trick that criminals think will get them out of a possession charge.)

One argument I see a lot is that Toledo was perfectly compliant. Often these arguments are based on misinformation. For example:

Goldman, whom I follow on Twitter and about whom I formed a favorable opinion during the first Trump impeachment, has this wrong. First of all: “perhaps” Toledo was running because he had a gun? Please. Don’t insult our intelligence by acting like this is a question. Of course he was running because he had a gun! Also, Goldman’s claim that the officer “told him [Toledo] to turn around” is not evidenced on the video above. Here is my own transcript of what the officer says beginning with the moment the sound starts at 1:58:

Police! Stop! Stop right fuckin’ now! Hands! Show me your fuckin’ hands! Drop it! Drop it! [sound of gunshot]

The cop did not tell Toledo to turn around, and Toledo would have been better off to drop the gun and show his hands without making any other sudden movements. Again, he was in a tough spot at that moment — and so was the cop — but Toledo is one who put them both in that tough spot.

And it is a tough spot — a tougher spot than most people realize. Even civil rights leaders who regularly berate the police might sing a different tune if they were placed in the same situation that this cop was placed in. That’s not complete speculation on my part, either. If you have never seen it before, take the time to watch this video, in which a civil rights leader actually (to his credit) took the time and effort to experience some use of force scenarios.

His takeaway: it’s tougher than it looks, and a suspect’s compliance is far more important than he had previously realized.

What I wouldn’t give to make some of the Twitter armchair use of force experts I have seen in recent days undergo the same scenarios.

I hear a lot about the fact that Toledo was 13. But what is the relevance of his age supposed to be, when he is holding a firearm and then suddenly whirls around to face the cop, who does not realize Toledo has ditched it? A 13-year-old can pull the trigger as easily as an 18-year-old. And if you watch the CPD video, it’s clear that Toledo’s adult companion did the shooting that triggered the police response — and later handed the gun to Toledo. That, in case you were unaware, is very common, because 13-year-olds are almost never punished as harshly as adults for the same act. So gang members will often hand a firearm to a youngster . . . either after a shooting (as here), or sometimes in order to have the youngster do the shooting. In my experience, the latter is very common. So while it’s a tragedy that a 13-year-old was shot, his age really makes no difference to the officer’s decision.

I also had someone on Twitter speculate to me that this may be the first time Toledo ever handled a gun. Of course, this person had no idea whether this is true. There are been reports, which apparently cannot be substantiated, that at least one friend of Toledo’s, referred to him as “Lil’ Homicide” in a social media post made after he was killed. Again: that may or may not be true. Whether it was or wasn’t — just like the Twitter speculation that he had never handled a gun — was all unknown to the cop, and really has nothing to do with the propriety of the cop’s decision.

Whether you think the cop’s actions were responsible, justified, reckless, or criminal — and there is room for rational people to debate all of this — the media ought not portray Toledo as a fully compliant individual. He didn’t have to keep running. He didn’t have to make a sudden movement a split second after holding a firearm. But to the media, he is nothing but a victim — a young boy who did exactly as he was told. Here is a typical article about the event, designed to inflame the passions while shedding zero light on the facts:

Nice framing of the story, huh?

That officer, identified as Eric Stillman, yelled “Show me your fucking hands!” at Toledo, who then stopped, raised both of his hands above his shoulders, and turned left to face the officer. On video, Toledo and Stillman were now parallel, with the officer’s flashlight shining directly onto Toledo and his hands. In the next moment, Stillman yelled “drop it” — it is not clear if Toledo was holding an object — and fired a single shot into Toledo’s upper right chest. Toledo immediately crumbled to the ground.

Are you kidding me? The statement “[i]t is not clear if Toledo was holding an object” is pure horse manure.

If you still have any doubt, here is another angle of Toledo ditching the gun alongside the fence, in three screenshots.

Staying on the topic of the media, this was also lovely to see:

Great job, guys!

There is a lot more I could say about camera angles, hesitation in police shootings, and other factors relevant to this topic, but I find that I already said it all in this post from 2017 about the shooting of Daniel Shaver — another agonizing scenario where I had difficulty reaching a firm conclusion about the propriety of the shooting based on the public evidence. If you’re interested to read more, I suggest following that link.

Whether you do or don’t, I hope you have learned something about the Toledo shooting from this newsletter, and I hope that it gives fair-minded critics of the shooting (and such people certainly exist!) something to think about.

I think many people believe the police should never shoot first because risking death is their job. I don't.

This excellent and insightful analysis was well worth the wait. Members of the media (armchair media included) should feel compelled to understand “perception-reaction time” before reporting on cop-involved shootings. It can completely change one's first impressions (or the popular narrative). Also, I really appreciate that you don't take a side in this, but lay it out for readers to consider further because it's a very tough situation, indeed.