No, the Judge in the Arbery Murder Trial Did Not Say There Was "Intentional Discrimination" in the Selection of the Jury

The story is Too Good to Check for Big Media, which wants you to believe that systematic racism is embedded in the system, the facts be damned.

The usual suspects were thrown into a tizzy today by misleading stories about the jury selection process in the trial of the men accused of murdering Ahmaud Arbery. Apparently the jury will consist of eleven white jurors and one black juror. Some uninformed outlets published articles claiming that the judge overseeing the trial had said the defense had engaged in “intentional discrimination” but that he could not do anything about it because of “Georgia law.” Here is one of the offending tweets:

I encourage you to watch the video. I will transcribe the relevant part, which begins 33 seconds in:

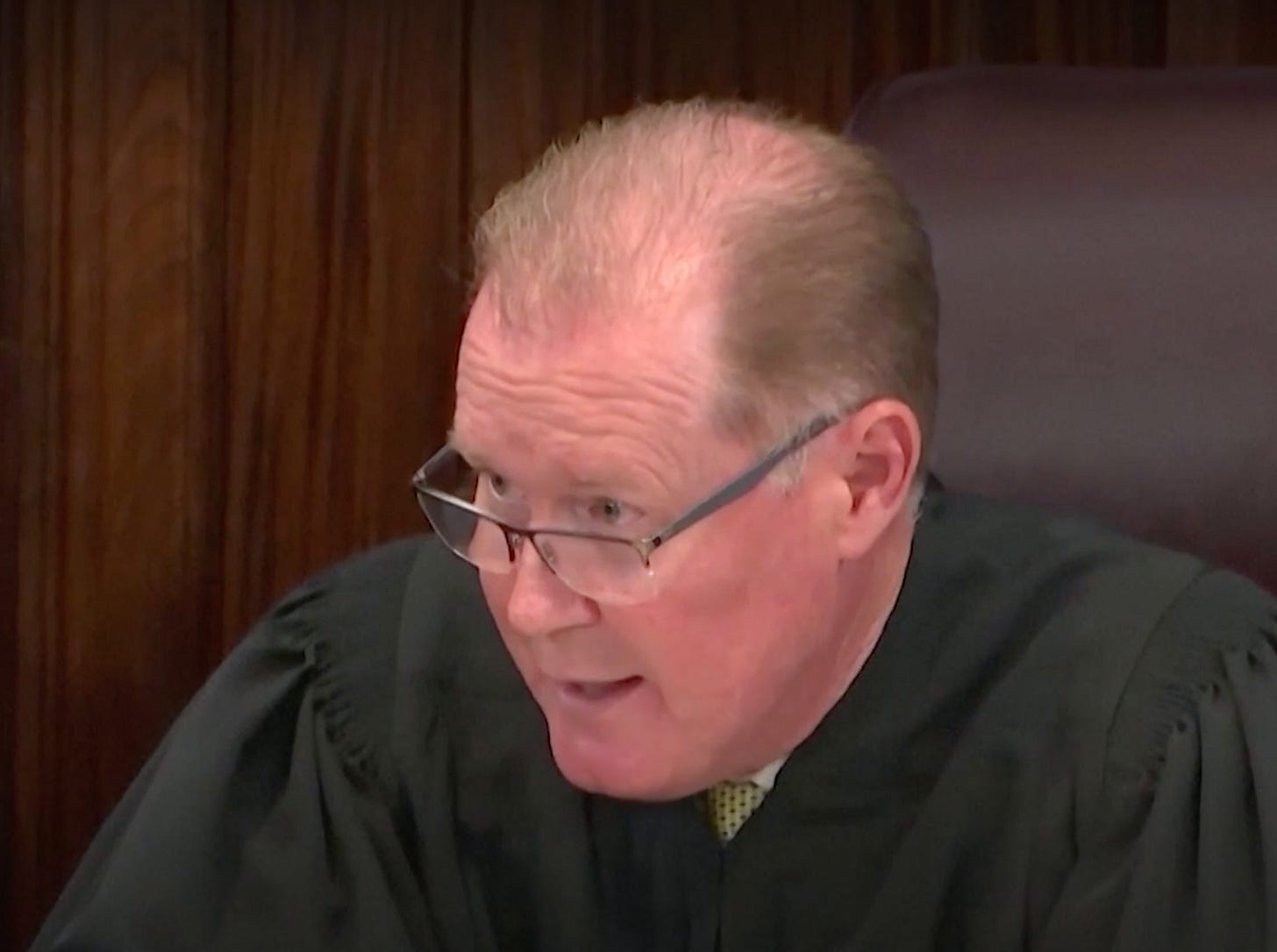

NARRATOR: On Wednesday, a judge rules that he’d seat the only one black juror and eleven white jurors despite prosecutors’ objections that several black potential jurors were cut because of their race. Superior Court Judge Timothy Walmsley even acknowledges this:

JUDGE WALMSLEY: This court has found that there appears to be intentional discrimination in the panel.

NARRATOR: But said Georgia law limited his authority to intervene.

Superior Court Judge Timothy Walmsley acknowledged that “intentional discrimination" by attorneys for the three white defendants charged in the death of the Black man appeared to have shaped jury selection. But he said Georgia law limited his authority to intervene.

CNN weighed in with an equally ignorant analysis:

The jury was selected after a two-and-a-half-week selection process that ended with prosecutors for the state accusing defense attorneys of disproportionately striking qualified Black jurors and basing some of their strikes on race.

Judge Timothy Walmsley said the defense appeared to be discriminatory in selecting the jury but that the case could go forward.

"This court has found that there appears to be intentional discrimination," Walmsley said Wednesday.

Oliver Willis, bless his heart, weighed in with a predictably dopey take:

Anyone who has ever tried a criminal case who read these headlines and watched these edited videos likely had the same reaction I had: Nah, that does not sound right. Let me see if I can investigate this further.

I soon found this New York Times video with a more extensive excerpt of the judge’s remarks, and everything made sense. Now, I’ll grant you that even this video has jump cuts, and I did not watch the trial live, nor have I seen an uncut video of the judge’s ruling. But based on the New York Times video, as well as reading that newspaper’s account of the proceedings, I’m reasonably confident I understand what happened. I am informed by my experience in handling criminal trials for nearly 24 years. Below, I’ll transcribe the more extensive remarks from the New York Times video, and then explain what’s going on here.

JUDGE WALMSLEY: This court has found that there appears to be intentional discrimination in the panel. That's that prima facie case. And I guess before I get into this, one of the challenges that I think counsel recognize in this case is the racial overtones in the case. [cut] Quite a few African-American jurors were excused through pre-emptory [sic] strikes exercised by the defense. But that doesn’t mean that the court has the authority to reseat [cut] The court is in a position where it’s got to make another finding, which is that the defendants are not genuine when they gave a reason, and that the reason they were claiming is not the real reason those jurors were struck. [cut] The court is not going to place upon the defendants a finding that they are being disingenuous to the court, or otherwise are not being truthful with the court when it comes to their reasons for striking these jurors. So because of that and because of, again, the limitations that Batson places upon this court’s analysis, I’m denying the motion.

The reference to Batson is not to “Georgia law” but to the United States Supreme Court case of Batson v. Kentucky, which outlawed the use of race as a factor in exercising peremptory (not “pre-emptory”) challenges. It’s not my intent to get too far into the weeds about the specific requirements of Batson and the manner in which it has been tweaked by subsequent cases. But the key thing to understand here is that when a lawyer in a criminal case accuses the other side of using race in its exercise of peremptory challenges, the judge employs a three-step process:

Prima facie case: The side making the motion (often the defense, but not always, as the Arbery case shows) must make a “prima facie case” that the other side is striking jurors based on “purposeful discrimination” on the basis of race. (There are other unlawful bases for the exercise of peremptory challenges besides race, but we’ll stick with race in this post to keep it simple.) At this point, the party making the motion need only raise an “inference” of purposeful discrimination. Often the showing is little more than: judge, look! He’s kicked a lot of black (or Asian, or white, or Hispanic) people!

Explanation: the accused lawyer then offers his or her explanation, meaning he or she just justify the challenge(s) with a race-neutral reason or reasons.

Decision: The court must then evaluate the proffered race-neutral explanation(s), and decide whether the party making the motion has proved purposeful discrimination.

Here’s how this would play out in a typical situation in the courtroom. The prosecutor strikes a black juror. The defense dramatically leaps up and demands to go sidebar. At sidebar, the defense speaks in a very loud whisper intended to be heard by the jury, and accuses the prosecution of racism. The three-step process might look like this:

Stage One: The defense says the prosecution has kicked eight jurors, three of whom are black. These are the only black jurors in the panel of twelve. The defense says it can’t see anything wrong with the black jurors kicked by the prosecution. Obviously, racism! The judge may or may not find a prima facie case, but may invite the prosecution to give its reasons even if it does not find a prima facie case, to protect the record in the event of an appeal. Keep in mind: this stage is the “prima facie” case. it requires only an “inference” of purposeful discrimination.

Stage Two: The prosecution then offers its reasons. In our example, the reasons might be: Juror #1 shouted “All cops are pigs! Defund the police!” and had to be admonished to calm down. Juror #2 has a father, mother, and two siblings in prison for various violent crimes, and said he thought they had all been treated unfairly by the system. Juror #3 dozed off three times while sitting in the box, once while the judge was speaking to him directly.

Stage Three: The judge finds that the prosecution did not engage in purposeful discrimination and denies the motion.

So that’s the process. Note that a judge might move the process on to Stage Two if the court initially finds even an “inference” of purposeful discrimination . . . and yet, the judge might ultimately make a finding that the party exercising the peremptory challenge(s) did not engage in purposeful discrimination.

And that, my friends, is what happened here. Ultimately, the court found no discrimination. This conclusion of mine is corroborated by the New York Times report I linked above:

After reviewing the eliminations one by one, Judge Timothy R. Walmsley of Glynn County Superior Court acknowledged that “quite a few African American jurors were excused through peremptory strikes executed by the defense.”

“But that doesn’t mean,” he continued, “that the court has the authority to reseat, simply, again, because there’s this prima facie case.”

The judge ruled that for each of the eight stricken jurors, the defense had provided a “legitimate, nondiscriminatory, clear, reasonably specific and related reason” as to why the potential juror should not be seated.

If the defense provided “legitimate, nondiscriminatory” reasons for their challenges, then they did not engage in purposeful discrimination. And that Recount tweet that Oliver Willis relied on left out the fact that the judge’s comments about intentional discrimination came at the prima facie stage, when only an “inference” of purposeful discrimination need be shown.

If you have watched the videos of the judge, you know that he is not the most articulate guy. He thinks peremptory challenges are “pre-emptory challenges.” His wording in finding that a prima facie case had been made was not the most articulate. But journalists have a duty either to understand what is going on, or to learn what is going on—especially when any rational person would raise an eyebrow at the way things appear at face value. If a judge seems to be saying “hey, there was lots of discrimination in this jury selection but them’s the breaks, what are ya gonna do, it’s Georgia law!” a rational person would wonder if they might be misunderstanding what the judge said.

But for Big Media, it’s a story that’s Too Good to Check. And a lot of people were misled today as a result.

I think that everybody who is expert in some field has had the same reaction when reading a confused media story about their field.

You have a rare talent for explaining legal concepts and events.