Where the University Presidents Went Wrong in the Stefanik/University Presidents Kerfuffle

It's the hypocrisy, stupid!

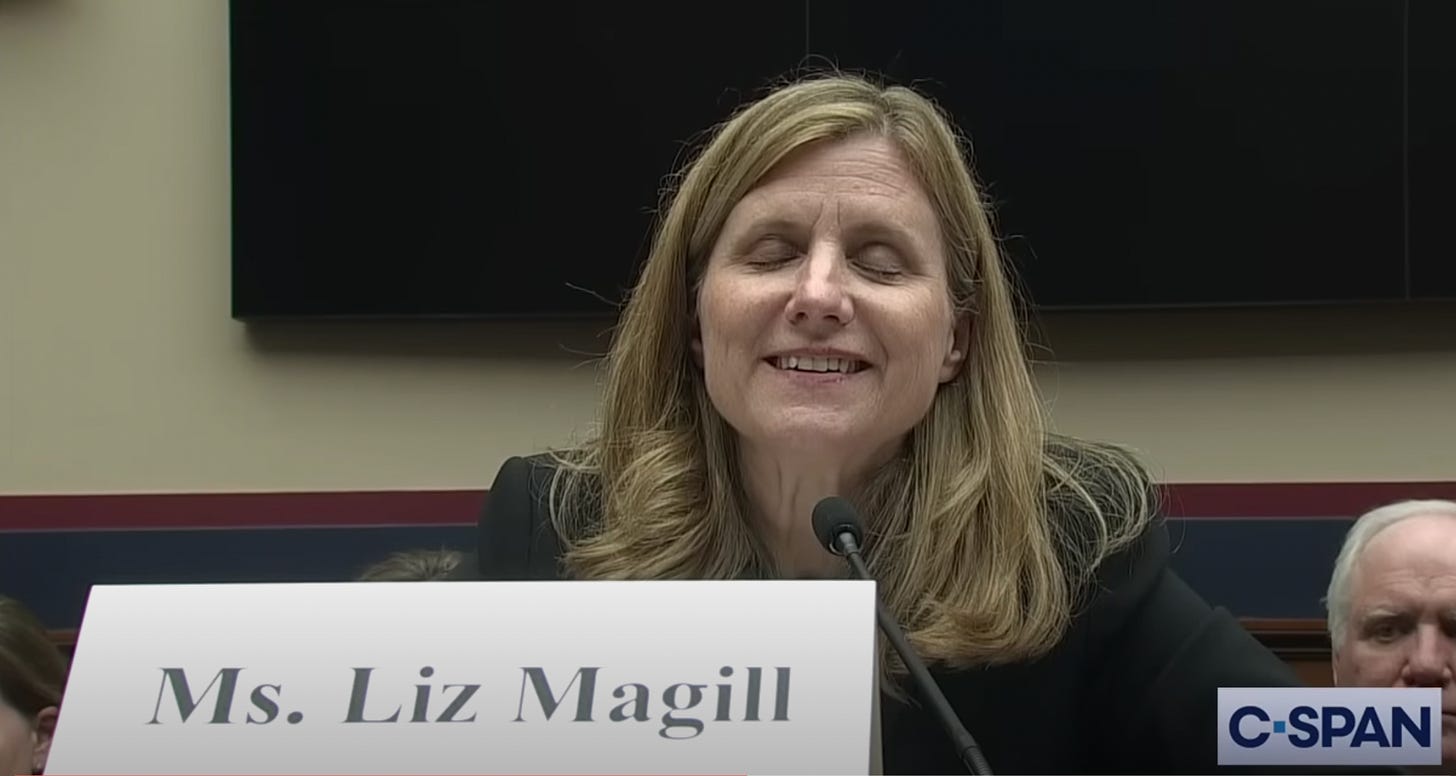

Above: The ex-president of the University of Pennsylvania just can’t believe the utter stupidity of the Congresswoman who is, at that moment, ending the president’s career.

Reader, I’d like to ask you a hypothetical question.

A student at a private university is standing on the main quadrangle of the campus. It’s a high-traffic area through which many, if not most, students must pass as they make their way to class. The student has a bullhorn, and he is shouting: KILL ALL THE BLACKS! A large mob, consisting entirely of other students, echoes his rhythmic chant. Each time he calls for the killing of all black people, the mob echoes his chant: KILL ALL THE BLACKS!*

Should this kind of conduct be grounds for discipline of the chanting students?

Does the answer depend on the context?

And the most salient question of all:

Does any sentient being reading this believe that any private university would allow such conduct to go undisciplined?

______

*You can substitute “TRANS PEOPLE” for “BLACKS” in these chants if it helps you see the point more easily. Also, in real life, a speaker actually holding such racist beliefs would probably be substituting a racial slur beginning with the letter “n” for the word “BLACKS” here. If a mental substitution of that word helps you internalize how distressing it would be for a black student to witness this chant, by all means, make that substitution.

Before we move on, let me provide some additional facts for the lawyers in the crowd, who are more likely than others to try to import nuances that I did not include in my hypothetical.

There exists on campus a dormitory whose rooms are primarily set aside for black students. White students are allowed to join, but most don’t, and the dormitory’s population is nearly 100% black. The mob I have mentioned is not outside the black dormitory. Nor is the mob outside schoolrooms devoted to African-American studies. No, the members of the mob are just on the main quad of the campus, where students of all colors and races routinely walk by.

Many black students do walk by this mob, and experience understandable distress—but nobody in the mob directly addresses them in my hypothetical. How do we know this is true? Because the mob consists of people wearing blindfolds. You see, some lawyer told them that if their invective is generalized and “diffuse” rather than targeting a specific student, their call for the genocide of all black people cannot get them in any trouble with the campus administration. So they wear blindfolds, to ensure that nobody can ever accuse them of targeting their genocidal chant at any particular student.

The students are all good, right? It’s all about that free speech, isn’t it? And clearly, these students are involved in free speech. Therefore, no college administrator would ever discipline these students! Nor should they!

Right?!*

_____

*Use of exclamation points may indicate some level of irony. — Ed.

Anyone following the news at almost any level is no doubt familiar with the recent hearings in which Chief Trump Apologist Elise Stefanik asked some smirking college presidents whether calling for the genocide of Jews violated their school’s code of conduct. If you somehow missed this controversy, the nuts and bolts were thoroughly covered at my blog in this post by my co-blogger Dana. The relevant videos are there for you to watch.

It’s been a few days since this happened, and I’ve tried to absorb some of the commentary that has come down since. In one camp you have honest champions of free speech, like Ken White, or FIRE, or Nicholas Christakis, as well as their compatriots like Jonathan Chait. These folks generally take a more absolutist view: the school presidents were right; it depends on context, and a lot of the uproar is a dishonest appeal to dopey populism.

In the opposite camp, you have the folks who echo Stefanik, and insist that there is no such thing as context here. If someone asks if genocide is wrong—or if it violates your code of conduct, which is just a lot of words that boil down to “it’s wrong”—the answer is simple: yes, genocide is wrong; yes, calling for genocide violates our code of conduct; yes, anything that Elise Stefanik wants to label a call for genocide really is one; and anyone who disagrees is a horrible anti-Semite.

I think I fall into a third camp. If I had to sum up my view—although, as you will see, you’re going to get a lot more than just a summary—my view would go something like this:

Genocide is wrong, and advocating it is wrong, and smirking when someone is asking you about it is dumb, even if that person is Elise Stefanik. Yes, context can matter, because context can always matter to everything, but let’s strip away the bullshit. It seems like the context that matters most to college presidents, when asked about speech targeting a particular group, is this: who is the group being targeted by the speech? Is it black people? Or trans people? Or . . . is it Jews?

Because if it’s Jews, then in that case, context matters quite a bit, dontcha know.

I think it’s high time these universities started applying a consistent standard. And, frankly, I don’t think they should allow the kind of intimidating mob gathering I described at the outset of this post. They don’t have to, in most cases, any more than Twitter has to allow onto its platform any speech protected by the First Amendment, including calls for genocide. Part of my mission here is to defend that point of view.

I’d like to structure this discussion by reacting to some of the commentary I’ve seen out there. The initial piece that made me want to write about this was written by Ken White: Stop Demanding Dumb Answers To Hard Questions. In it, Ken said the following about Stefanik’s grandstanding, and the reaction it provoked:

The college presidents did a rather clumsy job of saying, accurately but unconvincingly, that the answer depends on the context. Stefanik and every politician our loudmouth who wants you to hate and distrust college education and Palestinians pounced on it. And many of you fell for it. You — and I say this with love — absolute fucking dupes.

Hey! He’s talking about me! I thought. And while I agree with some of what Ken had to say, I dispute the contention that one must be an “absolute fucking dupe” to be angry at the responses and attitude of the college professors.

But First: Points of Agreement

First, I’d like to start with some points of agreement with Ken. Elise Stefanik is not a serious person. In fact, Elise Stefanik is an amoral fraud, who would readily cast aside every concept of civics and ethics that you and I hold dear, without taking a single moment for reflection, if jettisoning said principles would allow her to grasp even the smallest morsel of additional political power. I agree with Ken when he calls her “an unlikely standard-bearer for a crusade against antisemitism, given that she’s a repeat promoter of Great Replacement Theory, the antisemitic trope that Jews are bringing foreigners into America to undermine it.” She is, in my view, a soulless and unprincipled waste of oxygen.

If you think Stefanik is a Genuine Friend of the Jewish People who deserves Big Sincerity Points for her attacks on the college presidents, I urge you to watch Jake Tapper’s interview of Rep. Jamie Raskin, who recently asked Stefanik a few obvious questions that any actual Genuine Friend of the Jewish People would have no trouble answering—at least, that is, someone whose head was not clouded by an endlessly obsessive and feral craving to satisfy her ambition. You can read the questions here, and I’ll pick three of the best ones:

1. Is a candidate qualified to be president who hosted at his home for dinner Nick Fuentes, an avowedly pro-Hitler, Holocaust revisionist calling for a “holy war” against the Jewish people, and Kanye West, who vowed to go “death con 3” against Jews? Yes or no, Ms. Stefanik?

. . . .

4. Do you regret endorsing Donald Trump for president in 2016 just days after he tweeted an image of the Star of David superimposed over Hillary Clinton’s face and a thick pile of cash? Yes or no, Ms. Stefanik?

5. Are you prepared to renounce the antisemitic “great replacement theory”—which you have previously dabbled in and echoed in campaigns—which inspired the perpetrators of Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue, Buffalo, New York, supermarket and El Paso Walmart massacres? Yes or no, Ms. Stefanik?

Obviously, Elise Stefanik, that Great Friend of the Jewish People, is never going to criticize Donald Trump for anything Trump ever does or says, even if it’s having dinner with (and praising) a sleazy Holocaust denier like Nick Fuentes. If Donald Trump were to walk theatrically to St. John’s church and hold a copy of Mein Kampf over his head, Stefanik would find a way to defend Trump. She didn’t answer Raskin’s questions, of course, and she never will. She is a fraud.

Moreover, as I will discuss in more detail below, I agree with Ken that much of Stefanik’s goal is to suppress speech that either does not really amount to a call for genocide, or that arguably does not. And I agree that this poses dangers for speech generally. This is not an entirely black-and-white scenario.

Finally, I think there is always room to discuss “context.” Meaningful context can cause reasonable people to re-evaluate almost anything. That racist speech you thought you heard your neighbor making? That might actually have been your neighbor reciting lines from a play in which he is acting next week. Situation comedies and Shakespeare plays alike have often revolved around one character misunderstanding someone else’s motives due to missing context. And life is often full of scenarios that are less black and white than grandstanding politicians would have you believe.

But, as we will also see, context is not a catch-all. And I disagree with Ken about some of the specifics of his argument. I think that Stefanik’s initial question was a good one—and that we can divorce the content of the question itself, in the abstract, from the poor character of the person asking it, and the misguided implications that she no doubt intended.

Also, I think the college presidents’ answers were . . . less than perfect.

In Ken’s view, these opinions make me a credulous dupe who fell for Stefanik’s bullshit. But while I agree it’s not as simple as Stefanik portrays it, I also don’t think it’s quite as simple as Ken portrays it.

Private Colleges and Universities Generally Do Not Have to Follow the First Amendment—Plus, a Digression About the Way Universities Generally Behave

Ken acknowledges early in his piece that private colleges and universities (generally) do not have to follow the First Amendment—but then engages in a long discussion of the First Amendment anyway.

Even though private colleges aren’t bound by the First Amendment, let’s first look at it as a First Amendment question, as the outer limits of what’s permitted. Is calling for the genocide of a group protected by the First Amendment? In America, the answer is yes, unless it also falls into an established First Amendment exception. The First Amendment protects advocacy of the moral, historical, and practical correctness of monstrous, immoral, and illegal things, unless they are:

Conveyed as a true threat — that is a threat intended to be taken, and likely to be taken by a reasonable observer, as a sincere expression of intent to do harm to someone;

Conveyed as incitement — that is, intended and likely to cause imminent lawless action;

Part of a pattern of harassment — that is, directed to someone under protected circumstances (such as an employee or student) and meeting a stringent test for harassment, described below.

But what about college policies? Private colleges don’t have to follow the First Amendment, do they? With certain complex exceptions1 , no. [Ken’s footnote says that a constitutionally dubious California law “purports to require private universities to protect student speech as if it is governed by the First Amendment.”] But despite wall-to-wall propaganda about how American colleges routinely suppress any speech seen as remotely racist, many colleges have speech policies that are either vague or that protect speech rather broadly and robustly.

Whoa. I was about to discuss the issue of whether private universities ought to model their speech policies on the First Amendment, but I cannot let that bolded passage pass without extensive discussion. What was that Ken said again? It bears repeating, because it’s . . . striking. Ken said that “despite wall-to-wall propaganda about how American colleges routinely suppress any speech seen as remotely racist, many colleges have speech policies that are either vague or that protect speech rather broadly and robustly . . .”

This passage struck me as odd, especially coming from a guy who is calling other people “absolute fucking dupes.” Because the “wall-to-wall propaganda” in question has a very strong basis in fact. And the lovely and wonderfully robust free-speech policies that Ken lauds here don’t seem to provide a whole lot of protection to actual people on actual college campuses in actual situations where they offend a group favored by the left (read: “not Jews”).

I know Ken is aware of this body of evidence—but since he insists on calling it “propaganda,” I feel it’s important to take a few minutes to put some meat on this particular bone. I have recently begun reading The Canceling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott. This is a good source for this particular discussion, because I know that Ken, while not in sync with Lukianoff on the issue of cancel culture, shares with me a respect for Lukianoff and for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), to which both Ken and I have contributed (he far more than I, I suspect). Now, as I said, Ken and Greg do not entirely agree on cancel culture, and they have publicly discussed and debated their differences. My point here is not to suggest Ken agrees with Lukianoff on these issues. My point is to pick a source that we can all agree is not tendentious or politically hackish—which are, unfortunately, characteristics shared by many people who complain about cancel culture.

You’re about to hear about a few campus-centric examples taken from Lukianoff’s and Schlott’s book. Some of these you’ve heard about. Some you may not.

The first involves an “adjunct professor and graduate student at St. John’s University” named Richard Taylor, who was fired for giving a lesson about how China’s need for silver in the 1400s began the first cross-Pacific trading, leading eventually to the globalization that we see today. Why was this a fireable offense? Well, you see, the professor asked the class to discuss whether the positives of this move towards globalization outweighed the negatives . . . and one of the many issues mentioned in this class about trade and biodiversity was slavery. So, of course, some snot-nosed brat of a student filed a complaint saying he had been asked to justify slavery. This was not remotely fair, according to Lukianoff and Schlott—and I agree with them; you can view the PowerPoint presentation that Professor Taylor showed students here—but the controversy went viral, and that was enough to torpedo this young man’s teaching career.

Other stories include that of Gordon Klein, a UCLA professor who refused to grade black students differently after George Floyd’s murder. His email, which you can read here, explored some of the problems with the suggestion:

Do you know the names of the classmates that are black? How can I identify them since we've been having online classes only?

Are there any students who may be of mixed parentage, such as half black-half Asian? What do you suggest I do with respect to them? A full concession or just half?

. . . .

Remember that MLK famously said that people should not be evaluated based on the ‘color of their skin.’ Do you think that your request would run afoul of MLK's admonition?

UCLA suspended the professor, and he was reinstated only after FIRE got involved.

If you’re a reader of my blog, you’ve heard me talk about Greg Patton before. He is the USC international business professor who, in a part of a class on public speaking patterns, mentioned that the Chinese have a word that they often repeat as a filler word that is pronounced like nega. Several delicate flowers flipped out, and USC offered counseling to the poor dears who were so negatively affected, while taking Patton’s class away from him. It took a weeks-long investigation and plenty of outrage from alumni and bad press nationwide to convince USC that Patton had done nothing wrong.

Lukianoff and Schlott offer one more example: a professor whose inorganic chemistry course syllabus made a reference to the “Wuhan Flu or Chinese Communist Party Virus.” The professor explained that his intent was to “mock the euphemistic conventions of PC culture.” FIRE sent a letter to Syracuse University and he was eventually reinstated after a half-year suspension.

I’ll add one of my own, which I have discussed here on Substack before: the famous case of a music composer and professor (and survivor of the Chinese Cultural Revolution) having his seminar on Verdi operas cancelled for the offense of showing his class what is perhaps the most famous performance of Othello (the play) in history: Laurence Olivier’s iconic portrayal of the Moorish general in the 1965 film. (Now a microaggression, or worse, because Olivier wore black makeup for the role.)

Universities fly off the handle about racial and ethnic speech all the time. These are just a few examples, but Lukianoff and Schlott emphasize that the number of cases has skyrocketed in recent years.

Ken White’s Examples Don’t All Show That Context Matters to Whether Calls for Genocide Violate School Policies

So getting back to Ken’s piece, where was I? Ah yes, he says private colleges (generally) don’t have to follow the First Amendment, but asks us to “first look at it as a First Amendment question, as the outer limits of what’s permitted.” OK, but as we do, let’s also keep firmly in our mind that colleges and universities have it in their power to restrict some of the speech that Ken explains is protected by the First Amendment.

As the block quote I provided above shows, Ken reminds us that the First Amendment protects a lot of monstrous speech, as long as it is not a “true threat” or “incitement” or “part of a pattern of harassment.” He then has the line that distracted me above about the “propaganda” that colleges “routinely suppress any speech seen as remotely racist” but in fact have policies that, when not vague, “protect speech rather broadly and robustly.” (Eyeroll.) Ken notes how Harvard’s policy mirrors the standards in Title IX—which, according to the Supreme Court, provides that harassment is actionable only when it is “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and that so undermines and detracts from the victims' educational experience, that the victims are effectively denied equal access to an institution's resources and opportunities.” That and similar language is often quoted by FIRE in letters to universities with similar policies, like the letter linked above from FIRE to Syracuse University about the “Wuhan virus” professor. Ken concludes:

So. The university presidents were completely right. Whether calling for the genocide of the Jews, or any other group, violates a school’s policy depends on the context. For instance:

Going to a campus chapter of Hillel and chanting “kill all Jews” is probably so severe, objectively offensive, and destructive of students’ educational experience that it violates the standard.

If four students are talking politics in a dorm room, and one (by dramatic convention, a sophomore) says “we should just wipe all the Palestinians out,” and one of the four repeats that to someone else later, and that person is horrified, that is almost certainly not severe or pervasive or contextually destructive of the educational experience enough to qualify.

If a professor uses the Israel-Palestinian conflict to discuss whether armed revolution is morally or legally justified, and presents the argument that armed revolution by Palestinians is justified, that almost certainly doesn’t violate the standard, although some people argue that it inherently calls for the genocide of the Jews.

If a professor reads out sentiments expressed by different groups in a discussion of the war in Israel, and sentiment one the professor mentions is “kill the Jews,” that does not qualify. If you think that’s a silly example, you’re wrong.

If one student makes a point of saying “all Jews should die” to a classmate every time they meet to express a sentiment about Israel, that’s probably severe and pervasive enough to qualify.

If a student says, at a rally about Palestinian rights, “they want to kill all the Palestinians, but I say they should kill all the Jews first,” the context probably means that’s not severe, pervasive, or destructive of the educational experience enough, since it’s expressly conditional and political.

Let’s take a closer look at those examples and what they’re cited to prove. The first thing to notice is that—although Ken claims that these examples show that whether “calling for the genocide of the Jews, or any other group” violates school policy depends on context—some of the examples do not, in fact, actually portray someone calling for the genocide of the Jews, or any other group.

For example, if a professor “presents the argument” in class that “armed revolution by Palestinians is justified,” that fails to constitute an example of “calling for the genocide of the Jews, or any other group” in at least two ways. First, as Ken notes, it is at least arguable whether calling for armed revolution by Palestinians is equivalent to calling for genocide, and reasonable people can and sometimes do argue otherwise. But even more fundamentally, presenting an argument in class is not the same thing as calling for a particular action. If a professor in a history class describes the motives behind the Holocaust, and then decries those motives and systematically dismantles the alleged logic supporting those motives, he still could be said to have “presented an argument” for genocide, even though he never signaled agreement with it and indeed signaled strong disagreement. So Ken’s example here does nothing whatsoever to show that the context decides whether “calling for the genocide of the Jews, or any other group” violates school policy.

The same goes for the next example, which similarly involves a professor simply presenting a point of view and throwing it open for discussion.

Side note: if you follow Ken’s link showing that the example is not “silly,” you find . . . more of that “wall-to-wall propaganda about how American colleges routinely suppress any speech seen as remotely racist.” Because the link goes to a story about a professor being suspended for quoting James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates as part of a discussion over the use of the N-word:

In an honors seminar called the Scholar Citizen, Adamo introduced Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. In Adamo’s retelling, a student in the class quoted this sentence from early in the book: “You can really only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a n-----.” (Baldwin uses the full word, as did the student in class.) Students were shocked, Adamo said, and he asked whether, in an academic context, quoting from an author’s work, "it was appropriate to use the word if the author had used it.” In so doing, he used the word, not the euphemism.

Class discussion lasted about 40 minutes, he said, and ended in consensus that the word was too fraught to use going forward.

A similar discussion happened in a section of the course later in the day, Adamo said. After class, he sent all students a short email with links to two essays that he said pertained to the day’s talk. The first, by Andre Perry, David M. Rubenstein Fellow at the Brookings Institution, says to “choose to only use the N-word judiciously, reminding ourselves of its gravity by not using it loosely.” The second essay, by Ta-Nehisi Coates, formerly of The Atlantic, appeared in The New York Times in 2013, and has what Adamo called a “provocative title” -- “In Defense of a Loaded Word." But it concludes that “N----- the border, the signpost that reminds us that the old crimes don’t disappear. It tells white people that, for all their guns and all their gold, there will always be places they can never go.”

The professor was suspended, which I would not have thought possible given that Augsburg had “speech policies . . . that protect speech rather broadly and robustly.” (Irony alert!) As FIRE pointed out in a piece denouncing the suspension,

Augsburg’s Student-Faculty Bias/Discrimination Reporting Policy states in its introduction the university’s “commitment to academic freedom, which lies at the heart of Augsburg’s educational mission,” which “ensures each member of the community is free to hold, explore, or express ideas, however unpopular, without censorship or fear,” even “when those ideas challenge, disturb, or offend, as they inevitably will in diverse communities.”

Despite that “robust” policy, it took FIRE sending a letter to Augsburg for the professor to be reinstated. And now you know . . . the rest of the story.

In short, examples of professors presenting arguments or discussing points of view are not equivalent to calling for genocide, so providing examples of such classroom discussion does not show that “[w]hether calling for the genocide of the Jews, or any other group, violates a school’s policy depends on the context.”

We can also move quickly past the examples where Ken agrees that a particular call for genocide does indeed constitute harassment that would violate almost any school’s harassment policy, like “[g]oing to a campus chapter of Hillel and chanting ‘kill all Jews’” (we will come back to that one) or making a point of saying “all Jews should die” to a particular classmate every time you see him. That is harassment, and we all agree it is harassment. Yay!

That leaves two more examples:

If four students are talking politics in a dorm room, and one (by dramatic convention, a sophomore) says “we should just wipe all the Palestinians out,” and one of the four repeats that to someone else later, and that person is horrified, that is almost certainly not severe or pervasive or contextually destructive of the educational experience enough to qualify.

If a student says, at a rally about Palestinian rights, “they want to kill all the Palestinians, but I say they should kill all the Jews first,” the context probably means that’s not severe, pervasive, or destructive of the educational experience enough, since it’s expressly conditional and political.

Unlike the other examples, I think these examples do a pretty good job of making the point that “calling for genocide,” and whether that violates school policy, can be a context-specific concept. As I said above, context pretty much always potentially matters, in theory.

But the open secret—the thing that Ken does not really address, and the thing that offended most of us about the university presidents’ responses—is the issue of double standards. What if you substituted the word “blacks” for the disfavored groups in the above examples?

I think we all know the answer, but let’s talk it through, shall we?

The Real Problem: The Screaming, Obvious Double Standards at Work

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Constitutional Vanguard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.