If Trump Is Elected, Can He Really Order the Cases Against Him to Be Dismissed? I'm Not So Sure!

Ultimately, it's the judge's decision. Also: thoughts on the immunity decision, which has made presidents into kings.

Above: will Tanya Chutkan dismiss the January 6 case if Trump is elected president? Maybe not!

It is commonly assumed that if Donald Trump wins in November, upon assuming office he will order that the criminal cases against him be dismissed—and judges will do so without any fuss. This CNN story is typical of dozens of similar opinions you have probably seen in recent months:

November’s election will not only select the country’s next leader. It will determine Trump’s legal fate. If elected, it’s widely expected that Trump will make the federal prosecutions against him go away, either by ordering his attorney general to dismiss them or by pardoning himself.

You have no doubt seen variations of this claim all over the place, made by very smart people. For example, Ed Whelan, whom I respect a great deal, says this:

Allow me to make a controversial claim I have not seen anyone else make: I don’t think Trump can successfully get all of the charges against him dismissed . . . unless the Supreme Court of the United States rides to his rescue. I believe he will get the classified documents case dismissed (assuming the Eleventh Circuit revives it in the interim), but not the January 6 case, which will instead be put on hold until he is no longer president.

And the only way he can get around this is if a lawless Supreme Court intervenes to save him. Which, given the events of this past term, is a very real possibility.

In this Substack newsletter, I will explain the reasoning behind this perhaps shocking assertion of mine. Then, for paying subscribers, I will give my analysis of the immunity decision by which the Supreme Court placed the president of the United States above the law.

A Word About the Length of This Newsletter

This particular newsletter is over 21,000 words long. That’s the length of a short novella. It’s the equivalent of some 30 700-word essays. I have been writing it for weeks.

I note this for two reasons.

First, whenever there is a long time between my newsletters, I worry—because I know some people are paying good money to read what I have to say. I could be like other Substackers and spit out a couple of 700-word essays a week. If I did that, it would take me 15 weeks to write as much as I am putting out in this single post. If you’re a regular of this newsletter, you know I typically don’t do things that way, and you don’t expect me to. Usually the gap between posts is not this long, and usually the posts are not this lengthy. Today, I think both of my topics demand the length.

Second, I feel the need to respond to those who say: dude, I don’t have time for 21,000 words. What you need, my friend, is an editor. It is true that what I say in this post could, in a pinch, be condensed into 700 words. But if I did that, I would have to leave out a lot of compelling arguments. And more importantly, you would have to take a lot of what I say on faith. I have a lawyer’s aversion to simply making statements without support. I like to drive home my points with detail and extensive relevant quotations from original sources. Although I include links, my practice is to try to give you the content from those links within the post itself, so that the argument I present to you is self-contained and fully supported.

It’s a different experience than most Substackers provide. My style might be your thing and it might not. If not, that’s fine. I am actually considering writing up a shorter version of the free portion of this newsletter for publication in a more widely read venue, because I think the idea is original and deserves wider attention. But if detailed arguments are your thing, then baby, you have come to the right place. And I believe there is an audience for such discussions. It may be a smaller audience than many, but I consider it to be a discerning and important audience.

Where Have I Been?

Before I start, I’d like to include a brief side note (which you can feel free to skip over) to answer the question: just where the heck have I been, and why has it been so long since the last missive? If you don’t care, feel free to skip to the next heading, where the substance of the post begins.

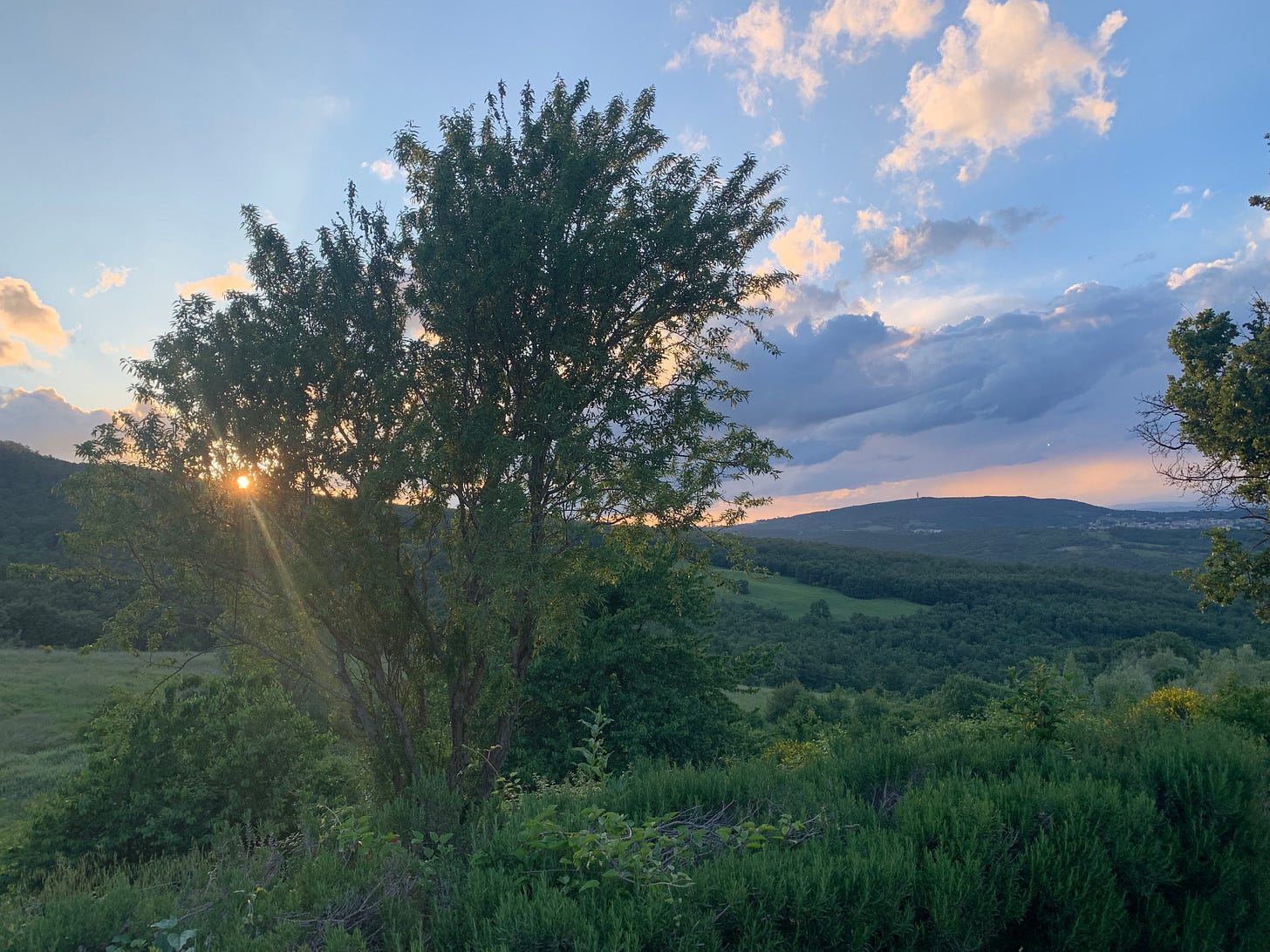

TRAVAILS OF A VACATIONING SUBSTACKER: I was out of the country for three weeks in Italy and Switzerland. It was truly the trip of a lifetime. The motivating factor for the trip was that a musical hero of mine—Sid Griffin of the legendary band The Long Ryders—was teaching a workshop in Tuscany. We six participants learned ten Long Ryders songs, mostly from the album Native Sons, and performed them in a live concert. Everybody got to sing and play electric guitar with a full band including a bassist and drummer. I even served as a sort of opening act, playing one of my own songs with Sid and the band. At the end of the week, I believed that if I died then, I would die a happy man. Here are a couple of photos I took from the property where we stayed, near Sarteano, Italy:

Lovely, huh?

Anyway, the verdict in the New York Trump trial came down during my vacation. I saw a bunch of ridiculous partisan arguments online about how the trial was supposedly terribly unfair to Donald Trump—and so, both during and after the vacation, I started writing a giant post refuting these arguments in detail, and arguing that (contrary to conventional wisdom) Trump deserves, and may receive, a custodial sentence. But I failed to publish that piece shortly after the conviction, and the topic was overtaken by other events. I figured I could finish it this month and publish it just before the July sentencing proceeding.

But now, of course, the sentencing has been delayed until September. And, to put it mildly, that sentencing has been overshadowed by certain other news events. Like the Trump immunity decision; one of two major candidates for president dropping out of the race; and the other candidate being the subject of an assassination attempt. You know, little things like that. Because the Trump immunity decision is in my legal wheelhouse, I will write about it in the second half of todays’s newsletter. I think I make an effective case that the immunity decision is one of the worst decisions the Supreme Court has ever issued.

But for now, I would like to move to my disquisition on a topic that recently occurred to me that I hope you find interesting: can Trump successfully get the cases against him dismissed once he is elected president? Everyone assumes he can. I’m not so sure!

Let’s begin by discussing a general principle in the law: whether to dismiss a case that has already been filed is a decision not exclusively within the purview of the executive. The judiciary gets a say too.

As a General Rule, the Judiciary Has a Degree of Authority Over the Question Whether to Dismiss a Criminal Case That Has Already Been Filed

It may surprise people to learn that, as a general matter, prosecutors do not have exclusive authority over the decision whether an already filed criminal case may be dismissed. Prosecutors do have exclusive authority over whether to file a case. A judge may refer a case to prosecutors. as Judge Otis Wright famously did in the Prenda Law case. But a judge can’t order prosecutors to file a case.

But once a case is filed, everything radically changes. The judiciary now has a say in what happens to the case. The extent of a judge’s power over such matters is shocking to some people. In some jurisdictions, the court has exclusive authority over such decisions.

For example, in California, Penal Code section 1386 states: “The entry of a nolle prosequi is abolished, and neither the Attorney General nor the district attorney can discontinue or abandon a prosecution for a public offense, except as provided in Section 1385.” Penal Code section 1385 states in relevant part: “The judge or magistrate may, either on motion of the court or upon the application of the prosecuting attorney, and in furtherance of justice, order an action to be dismissed.” Note the word “may.” The court is not required to dismiss a case on application of the District Attorney. As the California Court of Appeal explained in the case of People v. Viray (2005) 134 Cal.App.4th 1186:

A criminal prosecution, once filed, can now be dismissed only by a magistrate or judge on a finding that dismissal is "in furtherance of justice." (§ 1385, subd. (a).) If dismissal is sought by the prosecutor, he or she must "state the specific reasons for the dismissal in open court, on the record." (§ 1192.6, subd. (b).) This restriction extends explicitly to the "dismissal of a charge in the complaint" in a "felony case." (Ibid.; see People v. Konow (2004) 32 Cal.4th 995, 1021 [ 12 Cal.Rptr.3d 301, 88 P.3d 36] [magistrate erred prejudicially by failing to consider defense suggestion that complaint be dismissed in interests of justice].)

Under these statutes, the filing of a complaint divests the prosecutor of the power to unilaterally forgo prosecution. "Once a complaint is filed and the jurisdiction of the court or magistrate invoked, the power to dismiss is vested in the judge or magistrate. At that point the prosecution may only move the court for a dismissal. The court is not required to grant such motion."

(All bold emphasis in this post is mine.)

In a very famous example that is familiar to California criminal law practitioners of a certain age (ahem), a Superior Court judge famously refused to allow Los Angeles County prosecutors to dismiss the murder case against the Hillside Strangler, Angelo Buono. The New York Times reported on July 22, 1981:

A Superior Court judge today ordered Angelo A. Buono, a 46-year-old automobile upholsterer, to be tried for the 10 Hillside Strangler murders, ignoring a request from county prosecutors to dismiss the case because they had lost confidence in the credibility of their star witness.

. . . .

Legal observers here said that they believed the decision of Judge Ronald M. George was a first in the recent history of California in which a judge had ordered a defendant to face trial despite a request from prosecutors to dismiss charges against him.

The judge ordered the case tried ''in view of the overriding interest of society in having the issue of the defendant's guilt or innocence established by the conventional means of submission of a case to a jury.''

Judge George told the Los Angeles District Attorney, John Van DeKamp, that if the District Attorney’s office did not prosecute the case, Judge George would appoint the state’s Attorney General to prosecute. And that’s exactly what happened. Van DeKamp refused to move forward, and Judge George appointed the office of Attorney General, who at that point was George Deukmejian, to prosecute the case. By the time the lengthy trial was over, in a twist of fate, John Van DeKamp had been elected Attorney General! So it was his office that secured the conviction of Buono—a conviction that was upheld on appeal. Buono died of a heart attack in prison in 2002.

Van DeKamp later admitted that he had made a mistake not moving forward with the case.

Judge George’s actions were pretty extreme. I think they arguably invaded the executive’s sphere of authority—in a way that, as I will explain, would not be the case if a judge refused to dismiss Trump’s cases. But the important thing to note here is that, extreme or not, Judge George’s stratagem worked. Judge George was entirely vindicated, and he went on to become the Chief Justice of California.

OK, I hear you saying, I know you like talking about California law, Patterico, but what about federal law? Does federal law support what you’re talking about?

Why, yes, it does! Let’s discuss that next.

The Michael Flynn Case: How Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, U.S. Supreme Court Precedent, and Precedent in the Federal Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit Give the Judge a Role in Determining Whether to Dismiss a Pending Federal Criminal Case

As I was thinking about how the potential dismissal of the Trump charges might go in Federal District Court in the District of Columbia, I was reminded of the Michael Flynn case. That case is directly relevant to the question we are considering here, so we are going to discuss it in some detail. Fortunately, I did a lot of research into the Flynn case in 2020, which makes it easier for me to apply what I learned in the Flynn case to the Trump cases.

The Procedural History of the Michael Flynn Case

In the case of United States v. Flynn, the primary issue in the case ended up being the District Court’s ability to reject a Government request to dismiss, as governed by Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 48. Let’s revisit how this came to be. I will presume that the reader has some basic familiarity with the facts of the Flynn case. During Donald Trump’s campaign, General Flynn was caught on a wiretapped call with Russian Ambassador Sergei Kislyak (the CIA always wiretaps Russian officials to the extent possible) discussing how Donald Trump was going to undo sanctions imposed by President Obama over interference with the election. The FBI quizzed Flynn at the White House about his conversation with Kislyak, and Flynn lied to the FBI agents. That’s a crime, and charges were filed.

Flynn struck a plea bargain with Robert Mueller’s prosecutors in 2017. But the sentencing kept getting put over, and eventually nutjob Sidney Powell entered the chat, as Flynn’s new lawyer. She filed a flurry of insane motions making all kinds of wild accusations of governmental misconduct. Judge Emmet Sullivan denied these frivolous motions, and then Flynn moved to withdraw his plea.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump, entranced with Powell’s BS, was repeatedly grumbling about the case. Then Bill Barr entered the chat. Next thing you knew, the Government was asking for the case to be dismissed. The Government claimed to have new doubts about whether it could prove that Flynn had made false statements or that they were material. In reaching this position, the Very Serious and Not At All Corrupt Bill Barr and his cronies espoused a novel and ridiculously defense-oriented view of the “materiality” requirement—one that no U.S. Attorney had ever advocated to a court before, to my knowledge. Judge Sullivan was appropriately skeptical. Since there no longer seemed to be a party adverse to Flynn’s interests, and the whole thing stunk of corruption, Judge Sullivan decided to appoint an amicus to argue against dismissal.

Flynn then ran off to the D.C. Circuit, asking the federal Court of Appeals to: 1) order Judge Sullivan to grant the motion to dismiss, 2) vacate the appointment of the amicus, and/or 3) reassign the case to a different judge. Flynn got a dream panel. (Just how great the panel was for him, we’ll illuminate in a moment.) Judge Neomi Rao, whom I consider to be something of a Trumpist hack, wrote a decision basically denying that the District Court has any significant role in decisions over dismissing a pending case, and declaring that the Government’s (in my view) flimsy reasoning was entitled to a “presumption of regularity.” Judge Rao said the District Court had no business questioning prosecutorial discretion, characterizing the issue as one of the separation of powers. Rao’s 2-1 majority opinion ordered Judge Sullivan to dismiss the case. Judge Henderson, who had sounded oddly sympathetic to Flynn in the oral arguments, joined Judge Rao in this travesty of a decision.

Had matters ended there, I probably would have no basis to write this post. I disagree with the panel’s decision, vigorously, and gave my reasons for my disagreement at the time. But the law is the law.

But matters did not end there. Based on a suggestion from a member of the Court of Appeals, the D.C. Circuit took the case en banc and spanked Rao soundly. (More about the en banc court’s reasoning in a moment, but let’s finish the narrative of what happened.) How bad was the spanking? 8-2. Guess who the two dissenting judges were? That’s right: Judges Henderson and Rao, the two judges in the majority on the panel decision.

Remember how I said Flynn drew a dream panel? Out of the ten judges who participated in the en banc process, he drew the only two judges who agreed with him! And they had formed a 2-1 majority on the panel. But that panel majority was crushed by the en banc decision.

So: the case was sent back to Judge Sullivan, who questioned Sidney Powell about whether she had talked to President Trump about the case. Lo and behold, she had to admit that she had. President Trump pardoned Flynn in November 2020, and Judge Sullivan wrote an opinion granting the dismissal based on the pardon—but indicating that absent the pardon, he might well have refused to dismiss the case.

It’s worth looking in some detail now at the en banc court’s decision, as well as Judge Sullivan’s written opinion. The reasoning of the latter in particular is informative on the law that Judge Chutkan would have to follow if DOJ requested to dismiss the January 6 case.

The Flynn En Banc Decision

The Flynn en banc decision was not terribly enlightening on the underlying issue of Judge Sullivan’s power to reject the Government’s motion to dismiss. The D.C. Circuit did not conduct an extensive review of the law under Rule 48 (about which more below), or suggest that Judge Sullivan had the power to decline to dismiss the case. Instead, the court declined to issue a writ of mandamus in part because Sullivan had not yet decided the motion, and thus the vehicle of mandamus (an order to Judge Sullivan) was not necessary at that juncture—nor was dismissing the amicus. The Government also argued that the very procedure chosen by Judge Sullivan violated the separation of powers. Nah, said the en banc court. Slow your roll. Let the judge decide. The en banc court also refused to replace Judge Sullivan, explaining that “judicial rulings alone almost never constitute a valid basis for a bias or partiality motion.”

So the case returned to Judge Sullivan. Before we examine his opinion, let’s look at the rule that governs this situation, and its history.

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 48

Let’s start with the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. Rule 48 of those rules states in relevant part (again with my bold emphasis): “The government may, with leave of court, dismiss an indictment, information, or complaint.” The plain language of the text of the rule shows that the Government does not have exclusive authority to dismiss an information (which is, like a complaint, a charging document) or indictment. The prosecution must obtain leave of the court before any pending case can be dismissed.

The History of Rule 48

If you are interested in a comprehensive history of Rule 48 and its purpose, I recommend a law review article in the Stanford Law Review, by Harvard Law Professor Thomas Ward Frampton, titled Why Do Rule 48(a) Dismissals Require “Leave of Court”?

The Government has urged (and some commentators have opined) that Judge Sullivan has little choice but to grant the motion. The conventional view holds that it is necessary to distinguish between two types of motions to dismiss: (1) those where dismissal would benefit the defendant, and (2) those where dismissal might give the Government a tactical advantage against the defendant, perhaps because prosecutors seek to dismiss the case and then file new charges. The Government argues that Rule 48(a)’s “leave of court” requirement applies exclusively to the latter category of motions to dismiss; where the dismissal accrues to the benefit of the defendant, judicial meddling is unwarranted and improper. In support, the Government relies in part on forty-year-old dicta in the sole Supreme Court case interpreting Rule 48(a), Rinaldi v. United States. There, the Court stated that the “leave of court” language was added to Rule 48(a) “without explanation,” but “apparently” this verbiage had as its “principal object . . . to protect a defendant against prosecutorial harassment.”

But the Government’s position—and the Supreme Court language upon which it is based—is simply wrong. In fact, the “principal object” of Rule 48(a)’s “leave of court” requirement was not to protect the interests of individual defendants, but rather to guard against dubious dismissals of criminal cases that would benefit powerful and well-connected defendants. In other words, it was drafted precisely to deal with the situation that has arisen in United States v. Flynn: Its purpose was to empower a district judge to halt a dismissal where the court suspects some impropriety has prompted prosecutors’ attempt to abandon a case.

At this point I should note that the favorite case of the pro-Flynn crowd was the Fokker case: United States v. Fokker Servs. B.V. (D.C. Cir. 2016) 818 F.3d 733. The case has good language for the sort of folks who think courts should have no say over the dismissal of charges. It opens with this passage:

The Constitution allocates primacy in criminal charging decisions to the Executive Branch. The Executive’s charging authority embraces decisions about whether to initiate charges, whom to prosecute, which charges to bring, and whether to dismiss charges once brought. It has long been settled that the Judiciary generally lacks authority to second-guess those Executive determinations, much less to impose its own charging preferences.

(That language sounds categorical, but if you scrutinize it carefully, the word “generally” (which I bolded in the quote above) does a lot of work. We’ll return to that later.)

Fokker is a very complicated case to explain. It addresses the issue of “deferred prosecution agreements” or DPAs, in which the Government negotiates certain conditions with a company which, if fulfilled, allow the company to avoid a criminal conviction and everything that goes with it. Judges historically have tended not to scrutinize such agreements too closely, but around the time Fokker was decided, district courts had started to look at these agreements more aggressively. The Fokker case put an end to that, making reference to “the Executive’s long-settled primacy over charging” and holding that a court cannot reject a DPA based on the court’s conclusion that the negotiated conditions, or the prosecution’s charging decisions, were insufficient in the court’s eyes.

It sounds like a lot of power for the executive, doesn’t it? But Fokker needs to be viewed in the context of what it did analyze, what it did not analyze, and the authority it cited.

Fokker cited Rinaldi v. United States (1977) 434 U.S. 22 as its authority that courts have no “substantial role” in deciding whether to dismiss charges:

[T]he Supreme Court has declined to construe Rule 48(a)’s “leave of court” requirement to confer any substantial role for courts in the determination whether to dismiss charges. Rather, the “principal object of the ‘leave of court’ requirement” has been understood to be. a narrow one — “to protect a defendant against prosecutorial harassment ... when the [government moves to dismiss an indictment over the defendant’s objection.” Rinaldi v. United States, 434 U.S. 22, 29 n. 15, 98 S.Ct. 81, 54 L.Ed.2d 207 (1977).

Note the citation to footnote 15 of Rinaldi. Note also the use of the word “principal” in the bolded language. That’s another weasel word—and an important one.

In May 2020, on my blog, I wrote extensively about the application of Rule 48 in the context of the Flynn case, in several posts. On May 10, 2020, I authored a hypothetical transcript of a court hearing in the Flynn case, in which I imagined how Judge Sullivan might analyze the case. I noted that the key case from the United States Supreme Court applying Rule 48 is Rinaldi. The Government noted that Rinaldi held it was an abuse of discretion in that case for the trial court to deny a request to dismiss a case after entry of a plea. In footnote 15 of the case (yes, the same one cited in Fokker), the Court claims (contra Professor Frampton’s view based on the history of the drafting of the rule) that the “primary” purpose of the rule was to protect the defendant from harassment. But as I noted in 2020, the very same footnote also says:

[T]he Rule has also been held to permit the court to deny a Government dismissal motion to which the defendant has consented if the motion is prompted by considerations clearly contrary to the public interest.

The Supreme Court also stated in the opinion that the “salient issue” was whether the request for dismissal was “tainted with impropriety”:

The salient issue, however, is not whether the decision to maintain the federal prosecution was made in bad faith, but rather whether the Government's later efforts to terminate the prosecution were similarly tainted with impropriety.

The two bolded statements in the previous two block quotes are statements from the United States Supreme Court. They supersede any contrary authority from the D.C. Court of Appeals or any other court. As I said in a post on my blog published on May 12, 2020:

[T][he D.C. Circuit is the D.C. Circuit and the Supreme Court is the Supreme Court. And the D.C. Circuit can emphasize the “primary” policy of the Rule 48 leave [of court] provision all it likes. The Supreme Court of the United States has still said that is not the only policy consideration. A dismissal contrary to the public interest that is tainted with impropriety can still be rejected.

And so when the D.C. Circuit in Fokker says that “the Judiciary generally lacks authority to second-guess” the Executive’s decisions regarding “whether to dismiss charges once brought” . . . I would pay verrry close attention to that bolded (by me) word “generally.”

As I noted in that post, it is significant that the Rinaldi court favorably cited United States v. Cowan, (5th Cir. 1975) 524 F.2d 504, at page 513. Cowan overruled a district court decision to deny a motion to dismiss . . . but Cowan also examined the history of Rule 48 and stated: “It seems to us that the history of the Rule belies the notion that its only scope and purpose is the protection of the defendant.”

As an aside: I know it seems like we’re reading a lot into a couple of sentences and a footnote in a Supreme Court opinion. But Professor Frampton notes that Rinaldi “was summarily decided without argument or adversarial briefing” and “[n]either Rinaldi’s petition for certiorari nor the Government’s memorandum (also urging reversal) meaningfully addressed the history of Rule 48(a).”

Summing up, as I explained in my May 12, 2020 post:

What the Supreme Court is saying is: there are other objects besides the principal object. And one of those is an analysis of whether the motion was prompted by “considerations clearly contrary to the public interest.” And the favorable citation of Cowan certainly implies that those considerations are most certainly not limited to considerations that protect the defendant, but also to instances of “impropriety” that aid the defendant.

As I also made clear in my May 12, 2020 post, a district court’s role is still by nature very limited:

Let’s be clear: the courts will not uphold a refusal to dismiss the case because the judge has a strong feeling that the Government has weighed the benefit to the public interest inaccurately. If Judge Sullivan’s problem with the Government’s position is that Judge Sullivan would have thrown the book at Flynn if he were the prosecutor, that’s not enough to reject the motion. There has to be an “impropriety.”

So under the law as it currently stands in the United States Supreme Court, a court may not generally second-guess the executive’s decisions to dismiss by simply declaring that the court would have come to a different decision . . . but a court does have discretion to deny leave of court to dismiss a case in instances where the Government’s dismissal request appears motivated by impropriety contrary to the public interest.

With that background, let’s move to Judge Sullivan’s decision on remand.

Judge Sullivan’s Opinion on Remand

As I said earlier, Judge Sullivan’s opinion on remand allowed the case to be dismissed pursuant to Trump’s pardon of Flynn. We are concerned here with the portion of his opinion where he says he might have denied the Government’s request to dismiss. This issue was never litigated in the appellate courts, of course, because it was moot. But it is still worth looking at Judge Sullivan’s reasoning.

I won’t belabor the manner in which Judge Sullivan applied the law to the particular facts of the Flynn case. But the law he cited is important for the Trump January 6 case. And he says it very well. As you read the following description of, and quotes from, Judge Sullivan’s decision, imagine Judge Chutkan following a similar logical path in the Trump January 6 case. (I’ll imagine it more specifically for you below.)

Judge Sullivan begins at page 17 of his decision by citing the United States Supreme Court’s language in Rinaldi conceding that Rule 48 “obviously vest[s] some discretion in the court.” Rebutting the Government’s contention that this discretion exists only to protect the defendant, Judge Sullivan investigates the text, history, and precedent on Rule 48 to demonstrate that “courts have the authority to review unopposed Rule 48(a) motions as well.” He cites the Cowan case I mentioned above (the same Cowan case that I cited in May 2020 and earlier in this post) to the effect that “the history of the Rule belies the notion that its only scope and purpose is the protection of the defendant.” He cites the Thomas Ward Frampton law review article I cited above, which shows that Rule 48 was drafted in part to combat a perception “that prosecutors were seeking dismissals for politically well-connected defendants”—a scenario that made some judges “feel complicit in dealings they deemed corrupt.”

As Judge Sullivan explains, in 1941, the United States Supreme Court “appointed an Advisory Committee to create rules of criminal procedure.” That committee originally proposed a version of Rule 48 that had no “leave of court” requirement, but simply required the prosecution to state its reasons for a dismissal on the record. The Supreme Court clearly disagreed, pointing the committee to its past precedents indicating that the court still has a role in deciding whether to dismiss a filed case, even when a prosecutor confesses error. When the Committee still neglected to include a “leave of court” requirement in its final draft, the Supreme Court itself included that requirement. In the words of the Cowan case, which examined some of this history, the Supreme Court thereby made it “manifestly clear that [it] intended to clothe the federal courts with a discretion broad enough to protect the public interest in the fair administration of justice.”

Judge Sullivan noted that the case of U. S. v. Ammidown (D.C. Cir. 1975) 509 F.2d 538 also acknowledged that when a court weighs whether to grant a dismissal of a criminal action, Rule 48 gives the court a role in determining “whether the action sufficiently protects the public” in a way that prevents the “abuse of the uncontrolled power of dismissal previously enjoyed by prosecutors.”

This leads us to the Fokker case so beloved by the pro-Flynn crowd, which says the “principal object of the leave of court requirement” is “to protect a defendant against prosecutorial harassment.”

I am gratified to say that Judge Sullivan’s December 8, 2020 decision on this critical point largely mirrors the analysis I had already set forth months earlier in my May 2020 posts. He notes that Fokker “does not suggest that courts may only review opposed Rule 48(a) motions for prosecutorial harassment—the case simply quotes language from Rinaldi, stating that preventing harassment is the principal object of the rule.” And Judge Sullivan cites, and quotes . . . Rinaldi’s footnote 15! Regarding the notion that courts might examine dismissals to see if they are “prompted by considerations clearly contrary to the public interest,” Judge Sullivan accurately summarized the Supreme Court’s conclusion as leaving that issue open, “while also recognizing that courts, including the D.C. Circuit, have reviewed unopposed Rule 48(a) motions.

Judge Sullivan next considered the Government’s argument that the court does have a role to play, but it is “limited to determining whether the ‘decision to dismiss is the considered view . . . of the Executive Branch as a whole” as opposed to a “rogue prosecutor” dismissing a case on his own. Judge Sullivan responded with the excellent point that the “‘considered view of the Executive Branch as a whole’ could be contrary to the public interest.” Indeed, Judge Sullivan noted that in the appellate proceedings the Government had been so dismissive of this view, it even claimed that a court had no authority to second-guess a dismissal even if the court learned that the dismissal was the product of a bribe to the Attorney General.

(One can imagine John Roberts sagely nodding his head in agreement. But we’ll get to the immunity decision and Roberts’s slavish devotion to untrammeled executive power in the criminal context later.)

Judge Sullivan then held that a court may review a Rule 48(a) motion for “deficient reasoning or prosecutorial abuse.” He acknowledged that this was a narrow role for the court, but also emphasized that the Executive does not have “unqualified power or discretion.” He said courts must examine the record to make sure the dismissal is not (remember this language?) “tainted with impropriety.” Citing precedent from his circuit in Ammidown, Judge Sullivan ruled:

[A] judge may deny an unopposed Rule 48(a) motion if, after an examination of the record, (1) she is not “satisfied that the reasons advanced for the proposed dismissal are substantial”; or (2) she finds that the prosecutor has otherwise “abused his discretion.”

Judge Sullivan continued to cite Ammidown for the proposition that the court must be “satisfied that the reasons advanced for the proposed dismissal are substantial.” He cited Third Circuit precedent for the proposition that a Rule 48 motion may be denied if the dismissal is “contrary to the public interest.” But the judge may not second-guess charging decisions simply because the court’s conception of the public interest is different from that of the Executive. Citing other precedents, Judge Sullivan cited as examples of “prosecutorial impropriety” the following:

Dismissal “does not serve due and legitimate prosecutorial interests.” [citing Ammidown]

Dismissal is a “sham or a deception.” [citing Cowan]

Dismissal is based on “acceptance of a bribe, personal dislike of the victim, and dissatisfaction with the jury impaneled.” [citing Smith, a 4th Circuit case]

“[T]he corrupt dismissal of politically well-connected individuals.” [citing Woody (D. Mont. 1924) 2 F.2d 262, a case “well-known in legal circles” when Rule 48 was drafted, according to Professor Frampton]

I won’t dwell on the details of how Judge Sullivan applied these precepts to the Flynn case, as that case is not the subject of today’s missive. Suffice it to say that Judge Sullivan declared the whole issue moot because of Trump’s pardon of Flynn, but observed that the Government’s reasons for reversing course “appear[ed] pretextual.”

Judge Sullivan ultimately concluded:

Asserting factual bases that are irrelevant to the legal standard, failing to explain the government’s disavowal of evidence in the record in this case, citing evidence that lacks probative value, failing to take into account the nature of Mr. Flynn’s position and his responsibilities, and failing to address powerful evidence available to the government likely do not meet this standard.

Thus, the application of Rule 48(a) to the facts of this case presents a close question.

However, Judge Sullivan, due to Trump’s pardon, denied as moot the Government’s motion to dismiss—because he ended up granting dismissal based on the pardon.

Judge Sullivan’s reasoning seems to me to be sound, well supported by case law, and likely to serve as a blueprint for Judge Chutkan to follow in the January 6 case against Trump. So, armed with Judge Sullivan’s decision, let us now move to the Trump cases.

How Would It Actually Play Out if Trump Tried to Order the Cases Against Him to Be Dismissed?

Now that we have explained the applicable rules, it remains only to game out how things would actually play out when Trump orders the cases against him to be dismissed.

Let’s start with this: I think it’s almost beyond question that one of Trump’s first acts will be to fire Jack Smith and his entire team.

Indeed, the fact that everyone simply assumes this to be the case, and hardly anyone finds it shocking, just shows you how far the frog has been boiled over the last several years. It seems impossible to imagine now, but the very idea of then-President Trump firing Robert Mueller, who was then only considering whether to recommend criminal charges against Trump, was enough to send shock waves through the D.C. political establishment.

Sen. Lindsey Graham gave a stern warning Sunday to President Donald Trump against firing special counsel Robert Mueller.

“As I said before, if he tried to do that, that would be the beginning of the end of his presidency,” the South Carolina Republican said on CNN’s “State of the Union.”

That was March 2018. Doesn’t it sound quaint now? What a difference six years makes!

Anyway. So Trump fires Smith, and orders the Attorney General to dismiss the cases against him. Depending on when Trump gives the order, and who specifically is tasked with the job, there is the prospect of the mother of all Saturday Night Massacres.

Trump’s Order Could Easily Lead to Mass Resignations or Firings in the Department of Justice

In the absence of an order from Trump to dismiss the cases against him, the standard DOJ practice would be to ask the court to put the cases against him on hold until he is no longer president. It is the longstanding view of the Department of Justice and the Office of Legal Counsel that DOJ may not prosecute a sitting president. As I explained in March 2023, the Office of Legal Counsel (“OLC”) has twice opined, in 1973 and again in 2000, that a sitting president cannot be indicted or prosecuted while still in office. As I said then: “For better or worse, we’re stuck with this principle, at least for now. (I happen to think this opinion is highly dubious. For a good critique of the OLC opinions and related documents, I recommend this article by Walter Dellinger.)”

Of course, in that same piece, naive Patterico also said this:

Few things seem more obvious to me than the proposition that, if Donald Trump (or any president or ex-president) is guilty of a crime, he deserves to be prosecuted. You don’t get a pass on crimes because you are (or were) president. We do not have a king. No man is above the law.

Oh, you sweet summer child!

Anyway, like I was saying: DOJ policy is that you can’t move forward with the prosecution of a president while he or she is in office. (In fact, as we will see below in the section for paid subscribers, then-Judge Kavanaugh in his confirmation hearings said that the only issue regarding prosecuting presidents was timing, and that “I do not think anyone thinks of immunity.” But again: we’ll get to this hypocrisy/lying later.) So the correct and ethical way to handle the fact that Trump has been elected is to ask the court to stay proceedings until the end of Trump’s presidency.

But again: that won’t be good enough for Trump. He is going to insist that prosecutors move to dismiss the cases outright. I don’t know how easily that will go. Maybe he’ll get lucky and find compliant prosecutors right off the bat. I’d like to think not, and that he’ll have to run through several resignations—along the lines of the famous Saturday Night Massacre—before he finds someone willing to do his bidding. But eventually, he’ll find someone. What happens then?

Aileen Cannon Would Dismiss the Classified Documents Case Without a Second Thought—Assuming the Case Is Still Around

When I began writing this post, there still was a classified documents case. As I publish it, there is not. Judge Aileen Cannon in Florida has dismissed it, in a clownish opinion that airily dismisses on-point language from the Supreme Court. Her lawless decision has been appealed and will almost certainly be reversed by the Eleventh Circuit. (What the Supreme Court might do then is anyone’s guess. I no longer trust the Supreme Court to enforce the law when it comes to cases affecting Donald Trump.)

If the case is back in Cannon’s court by the time Trump orders the cases against him to be dismissed, Department of Justice prosecutors will march off to court in Florida and the District of Columbia and ask that the cases be dismissed. And Judge Cannon will do so. She is in the tank for Trump, as anyone who has followed the classified documents case already knows. There will be nobody with standing to appeal her decision. That case is going away forever.

But if I’m right, the judge in D.C., Judge Tanya Chutkan, will have something to say about it.

What Is Judge Chutkan Likely to Do?

I described the applicable federal law in the District of Columbia above. How will that play out? Let’s apply some of the basic principles articulated in Judge Sullivan’s decision, discussed extensively above.

In one of my 2020 posts about the situation Judge Sullivan faced, I imagined a court appearance on the motion to dismiss, and provided a fictional “transcript” of how I thought those proceedings might go. To me, such a fictional transcript is an effective way of imagining how the court might express itself, and how the Government might react. Even though this post is running long, I think the best way to do this—and the way that best helps me imagine what the Government’s and the judge’s respective views might be—is to write a version of the same type of imagined courtroom discussion in the next section.

So. All rise! Court is now in session.

An Imagined Hearing on the Motion to Dismiss the January 6 Case

JUDGE CHUTKAN: We are here on the Government’s motion to dismiss.

Let’s review the relevant timeline of this case. The indictment in this case was filed on August 1, 2023. After denying the defendant’s immunity motion, I stayed all proceedings on December 13, 2013, so that the appellate process could play out. The Supreme Court issued its ruling on July 1, 2024.

The Supreme Court remanded the case to the District Court with instructions for this Court to decide several legal issues, with the benefit of briefing. Those included:

A remand for this Court “to assess in the first instance, with appropriate input from the parties, whether a prosecution involving Trump’s alleged attempts to influence the Vice President’s oversight of the certification proceeding in his capacity as President of the Senate would pose any dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” The Supreme Court held that these actions are entitled to a presumption of immunity which it is the Government’s burden to rebut.

A remand for this Court to examine the allegations in the indictment relating to a conspiracy to convince state election officials to change their state’s electoral votes for Joseph R. Biden to electoral votes for defendant—and when that plan failed, a subsequent conspiracy to submit false slates of electors to Congress, to create a phony controversy over which certifications were valid, with the purpose of casting the Congressional vote count into chaos and ultimately swinging the election to defendant. The remand in this instance directs this Court “to determine in the first instance . . . whether Trump’s conduct in this area qualifies as official or unofficial.”

A remand for this Court to consider “various allegations regarding Trump’s conduct in connection with the events of January 6 itself” including the issuance of tweets and the delivering of a public address at the Ellipse. This Court was directed “to determine in the first instance whether this alleged conduct is official or unofficial.”

Due to Supreme Court rules regarding the issuance of a remittitur, the case returned to my court on August 2, 2024. I was out of the country in early August, and we returned on this case in the middle of August. I requested the parties to submit briefs addressing how I should conduct my inquiries on remand. The defendant asked that I rule on the various issues on the papers. And of course we know that the Supreme Court indicated that at a minimum, this Court would require briefing on these issues. As the Government pointed out, however, the Supreme Court also specifically stated that some of the decisions I would have to make would necessarily involve some degree of factfinding. For example, the majority opinion said that the issues regarding the defendant’s communications with state election officials and surrounding fraudulent slates of electors was an analysis that would be “fact specific, requiring assessment of numerous alleged interactions with a wide variety of state officials and private persons.” And the majority said that the issue of the defendant’s tweets and public speech was a “necessarily factbound analysis” that could require an investigation of “what else was said contemporaneous to the excerpted communications, or who was involved in transmitting the electronic communications and in organizing the rally.” The Government accordingly suggested that this Court hold an evidentiary hearing with witness testimony to address these various inquiries.

I found the Government’s position persuasive. After defendant was elected president, this Court began conducting those hearings. And then, on Monday, January 20, 2025, the defendant was inaugurated as president of the United States. On that morning, I ordered all proceedings in this case suspended until such date as the defendant is no longer president.

Subsequent to that, I received a motion from the Government indicating that it wishes this case to be dismissed. The motion also argued that it wishes me to lift the stay on the proceedings for the sole purpose of entertaining this motion to dismiss. The Acting Attorney General is appearing on the case this morning to argue the matter. And so I guess my first question is: do I even have jurisdiction to hear this matter?

I’ll hear from Mr. Paxton.

KEN PAXTON: Good morning, Your Honor. The court must grant the Government’s motion to dismiss. According to the law of this Circuit as discussed in the Fokker case, this Court may not second-guess the reasons for a dismissal, because, quote, "the Judiciary generally lacks authority to second-guess those Executive determinations, much less to impose its own charging preferences.” The Government’s position is that the only role for this Court is to ensure that this is not the motion of a rogue prosecutor. That is why I, the President’s Acting Attorney General, am personally appearing in the case, to make it clear that this is the position of the Government.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Well, before we get to the motion itself, I asked you whether I even have jurisdiction to entertain this motion. I have suspended all proceedings in the case.

KEN PAXTON: I assumed that the reason this Court suspended the proceedings was due to the fact that the defendant had taken the oath of office.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: That is correct. My reading of the law in this area is that a prosecution cannot proceed against a sitting president. Accordingly, I have suspended proceedings in the case until the next president is inaugurated.

KEN PAXTON: It is our view that this Court has no authority whatsoever to reject the Executive’s decision that the case should be dismissed with prejudice.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: OK, I am not so sure about that. But just so the record is clear, I will hear your arguments in more detail. Rule 48 says you must seek leave of court to dismiss a case. Why should I dismiss rather than continue to stay proceedings for the next four years?

KEN PAXTON: It is the Government’s position that the Court has no role in making any such determinations at all. As we argued in our papers, dismissal is exclusively within the Executive’s purview. This Court, as a part of the Article III judicial branch, simply has no authority to second-guess the Executive when it comes to a motion to dismiss. It would violate the separation of powers for the Court to arrogate to itself such a core executive power.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: I believe that under Rule 48 and under Ammidown I have a more substantial role than that, Mr. Paxton. And so, to make it clear for the record, I am today ruling that for me to grant leave of court for this dismissal, I must be “satisfied that the reasons advanced for the proposed dismissal are substantial” and that you have not abused your discretion in making the motion. I have the authority to deny this motion if I find the dismissal “contrary to the public interest.” And so today, I will examine whether the dismissal serves “due and legitimate prosecutorial interests,” or whether, on the contrary, it is instead a “sham or a deception.”

KEN PAXTON: This Court has no role—

JUDGE CHUTKAN: I understand your position, Mr. Paxton, but I have made my ruling on the law. You are free to take me up on appeal if I decide against you at the end of this hearing—although to be honest, I’m not sure the Court of Appeal will even hear the appeal, since I continue to believe all of these proceedings must be stayed. In any event, as I have agreed to hear you out, I want you to understand that the legal principles I have announced are the ones I will apply. I should add that I find that Rule 48 was drafted in part to prevent “the corrupt dismissal of politically well-connected individuals.” There is obviously no more well-connected an individual than the President of the United States, and it is my understanding from what I have seen in the newspapers that he is the one who ordered today’s dismissal. Am I correct in that assumption?

KEN PAXTON: We believe questions like that fall within the scope of executive privilege, and on that ground I respectfully cannot answer that question, Your Honor. I can say this, though: in my personal opinion as head of the Justice Department—

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Acting head of the Justice Department.

KEN PAXTON: —be that as it may, I assure this Court that this motion to dismiss is the considered decision of the Department of Justice, and as such it must be granted.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Let me ask you this. Assume, for the sake of argument, that you believed this to be a sound prosecution. What would you do?

KEN PAXTON: We do not consider it to be a sound pros—

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Let me stop you there. I am asking you a hypothetical. By answering my question you are conceding nothing about the validity of the case. I’ll make that clear to all the reporters here. (Laughter.) Accept my hypothetical. If you believed it to be a sound prosecution, what would be the position of the Justice Department? That the proceedings should be stayed, just as I have done, correct?

KEN PAXTON: As I believe the Court knows, it has been the considered opinion of the Department of Justice and the Office of Legal Counsel for well over 50 years—an opinion that was reaffirmed over 25 years ago— that “the indictment or criminal prosecution of a sitting President would impermissibly undermine the capacity of the executive branch to perform its constitutionally assigned functions.” Therefore “the constitutional structure permits a sitting to be subject to criminal process only after he leaves office or is removed therefrom through the impeachment process.”

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Meaning that if you thought this was a valid prosecution—

KEN PAXTON: We still could not bring it to trial or even litigate it.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Until President Trump left office, you mean.

KEN PAXTON: As I said, we do not believe this case—

JUDGE CHUTKAN: We’re still accepting my hypothetical.

KEN PAXTON: Under the OLC opinions authored in 1973 and 2000, a sitting president is immune, not merely from prosecution, but even from indictment alone. The opinion reasoned that a pending indictment “will spur the President to devote some energy and attention to mounting his eventual legal defense.”

JUDGE CHUTKAN: But don’t the OLC opinions acknowledge that the distracting nature of the pending indictment “may be less onerous than those imposed on the President by a full scale prosecution”?

KEN PAXTON: That is true. But if the Court continues reading beyond that quote, it will see that the opinion indicates that “the public interest in indictment alone would be concomitantly weaker assuming that both trial and punishment must be deferred, and weaker still given Congress’ power to extend the statute of limitations or a court’s possible authority to recognize an equitable tolling.” And when the opinion balanced those competing concerns, it concluded that a sitting president should be “immune from indictment as well as from further criminal process.” The opinion said the president cannot be indicted because the prospect of preparing his defense would distract him from performing his presidential duties.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: But that is not the question here. President Trump has already been indicted.

KEN PAXTON: The Government’s argument is that he cannot face a pending indictment for the same reasons.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Well, I am of course not bound by the OLC opinion. But would staying the case again really cause the president to spend all his time defending against the case? He had four months to prepare for trial between the indictment and the date I stayed proceedings. He has had nearly six months more to prepare for trial since the time the case returned to this Court. That’s ten months total.

KEN PAXTON: President Trump has been pretty busy with other matters during that time.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Frankly, that’s not my problem. In this courtroom, sir, the defendant is simply the defendant. But in terms of the relevant issue, according to the OLC opinion, the issue is whether he will be distracted in his presidential duties due to his need to prepare the case.

And here’s the thing, Mr. Paxton. It took nearly seven months for the appeals in the first immunity decision to be resolved—and I have read that the D.C. Circuit and the Justices of the Supreme Court considered that to be an “expedited” timeline. So as I was saying, before being sworn in, the defendant had ten months to prepare the case.

After he is no longer president, we will see if the Justice Department under the next president wishes to proceed with the case. Maybe they will decide not to.

If the Justice Department under the next president does decide to move forward with this prosecution, there is still work for this Court to do. I need to complete my evaluation of the issues that the Supreme Court remanded to me. The defendant was already prepared to do that, as that hearing has already started. Then there will likely be a new round of appeals, possibly again to the Supreme Court. I will not count that time, or the time the defendant served as president, against the defendant. I will not consider it to be time he has to prepare. As before, the case will be stayed during that time, and I have consistently ruled that the defendant need not take any action on the case, including preparations for trial, while proceedings are stayed. Accordingly, if and when the case returns here for trial, which is by no means certain, I can certainly entertain any motions from the defendant at that time seeking more time to prepare. So I do not see his need to prepare for the case as interfering with his presidential duties, and I will not dismiss this case on that basis.

That leaves us with our basic Rule 48 analysis. As I said, I believe I am entitled to conduct a limited examination of whether the requested dismissal is in the public interest. The Supreme Court of the United States, in ensuring that Rule 48 retained the leave of court requirement, has ensured that the judiciary has a legitimate role in making such decisions. As the Supreme Court held in Rinaldi, I must examine “whether the Government's later efforts to terminate the prosecution were . . . tainted with impropriety.” I can think of no situation more “tainted with impropriety” than the action of a criminal defendant ordering the dismissal of his own criminal case. Such an order strikes me as the most obvious example of self-dealing imaginable, and seems a far greater invasion of the separation of powers than this Court denying dismissal of a case already filed and properly in my courtroom. My analysis is bolstered by the history of Rule 48 as set forth in the Frampton law review article I have cited, which states that part of the rule’s purpose was to discourage “dubious dismissals of criminal cases that would benefit powerful and well-connected defendants.” Who is more powerful and well-connected than the president of the United States—a man who has the power to order the Department of Justice to commence or to dismiss any criminal case, including one against the president himself?

That is a rhetorical question. (Laughter.)

As for the interests of the Executive Branch in making these determinations, I am not supplanting the Court’s judgment for that of the Executive for all time. If a Department of Justice not answerable to the defendant himself asks me to dismiss this case, I will take that request very seriously. The specific “taint of impropriety” I have just described, caused by the request for dismissal being made under the authority of the defendant himself—will be gone. And given the absence of that compelling factor, the taint of impropriety may well be sufficiently diminished for me to consider dismissal.

That, however, is a question for the future. As for now, your motion is denied.

KEN PAXTON: We are giving notice that we intend to appeal this ruling, to the Supreme Court if necessary.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: I expected no less.

KEN PAXTON: President Trump may just pardon himself.

JUDGE CHUTKAN: Whether he can do that is by no means certain—but in any event, it is a question for another day. That ends this hearing.

The Supreme Court (or Even the D.C. Circuit) to the Rescue?

Let’s not get too excited. As our hypothetical Acting AG Ken Paxton just suggested, the Supreme Court may indeed step in to save Trump—either by rubber-stamping a self-pardon (the constitutionality of which is beyond the scope of this already long piece) or by issuing a Rule 48 decision quite at odds with what they said in Rinaldi.

But they may not even have to do that. I’m not sure that a ruling such as the one I have described would withstand appeal at the circuit level. At the D.C. Circuit, there are plenty of skeptics of a significant judicial role in Rule 48 dismissals. The Fokker case, which is the most recent substantive pronouncement in this area, was written by Judge Srinivasan, who is the Chief Judge of the D.C. Court of Appeals. And you’ll the recall the stark declarations of the opening paragraph of that decision: a paean to executive power, albeit sprinkled with lawyerly qualifying words (such as “the Judiciary generally lacks authority to second-guess those Executive determinations” or “[t]he courts instead take the prosecution’s charging decisions largely as a given”). Yes, Judge Srinivasan also wrote the en banc decision in the Flynn case, but that was not a decision brimming with enthusiasm for the idea that trial judges should involve themselves in second-guessing Rule 48 dismissal requests. The basic idea of the en banc decision was to give Judge Sullivan a chance to make a decision before being taken up on a writ. That en banc decision, to my reading, is fairly dripping with language that Judge Sullivan could have taken as a warning: we’ll give you a chance to do the right thing and keep your nose out of this Executive decision, buddy, but step out of line one time and we’ll be right here!

As for the justices of the Supreme Court . . . well, they are more than a bit protective of executive power. As we are about to see, in our discussion (for paid subscribers only) of the Trump immunity decision, they have proclaimed (citing Justice Scalia’s dissent in Morrison v. Olson) that “investigation and prosecution of crimes is a quintessentially executive function.” My guess is, if Judge Chutkan takes the path I have suggested here, the Supreme Court will bail out Trump once again. But I think the road to get there will be far bumpier than most critics have anticipated. It could take years and be very controversial. If that proves to be the case, I’ll be right here to remind you I said so. (And if it doesn’t, you’ll never hear another word from me on the topic!!)

Let’s tackle the Trump immunity decision now. If you’re a paid subscriber, buckle up. I have a few things to say about that too.

The Trump Immunity Decision: One of the Most Shameful Episodes in Supreme Court History

I can’t sugarcoat this. I think the decision in Trump v. United States is destined to go down as one of the most shameful decisions in Supreme Court history, along with cases like Dred Scott, Plessy v. Ferguson, and Korematsu. The reason is simple. Our country was founded in large part on the principle that no man is above the law. That principle is gone. And the Supreme Court has killed it, with a little help from Donald Trump.

I am not entirely alone in this opinion. Ken White (“Popehat”) had this to say:

This is a catastrophically bad decision by the United States Supreme Court. And the bottom line is, I think it makes it functionally impossible to reliably prosecute a former president, particularly Trump. So even if it doesn't give absolute immunity, on its face, for crimes committed while president, it comes so close, it basically makes no difference that it doesn't. . . . I really do not hesitate in saying this is a completely shocking decision.

And Nick Catoggio (“Allahpundit”) had this to say:

To say that it placed the president above the law isn’t quite right. It’s more accurate to say that, as of Monday, with respect to his most menacing and potentially tyrannical powers, the president is the law.

Within two years, probably less, this will be widely viewed as the most infamous decision ever rendered by the Roberts Court.

. . . .

This decision will be John Roberts’s legacy as a judge. Trump will see to it. And Sonia Sotomayor, the chief dissenter from the ruling and the author of that parade of horribles, will end up with one of the easiest “vindicated by history” opinions in the long life of the court.

. . . .

“You’ll regret this,” Mitch McConnell once famously warned the other party after an especially terrible decision of its own, “and you may regret this a lot sooner than you think.” We’ll regret this sooner than we think.

I subscribe entirely to these points of view. And I have to say: I think one of the main reasons Ken and Nick feel this way is because they are smart lawyers who have read the decision. As for people defending the decision, I have noticed that many of them make arguments that inadvertently reveal they never bothered to read it at all.

The main debate I see about this decision is between those on one side who say: “Calm down. This decision does not allow anything that extreme, and anyone who says otherwise is hysterical” and those on the other side who say: “I think the decision does, in fact, eliminate criminal liability for a range of very scary actions by a president, including assassinations of political rivals and military coups.”

I am distinctly in the latter camp, and the principal aim of what follows is to explain why—with reference to the text of the decision, which (like Ken and Nick, and unlike many members of the “calm down” crowd) I have read.

Before I get to the nuts and bolts of the decision, I’d like to talk about the general problem the Supreme Court was confronting, and what most people expected the likely resolution to look like.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Constitutional Vanguard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.