David French Cites Weak Evidence to Show Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System

I respect David French, but on this topic, his proof is wanting.

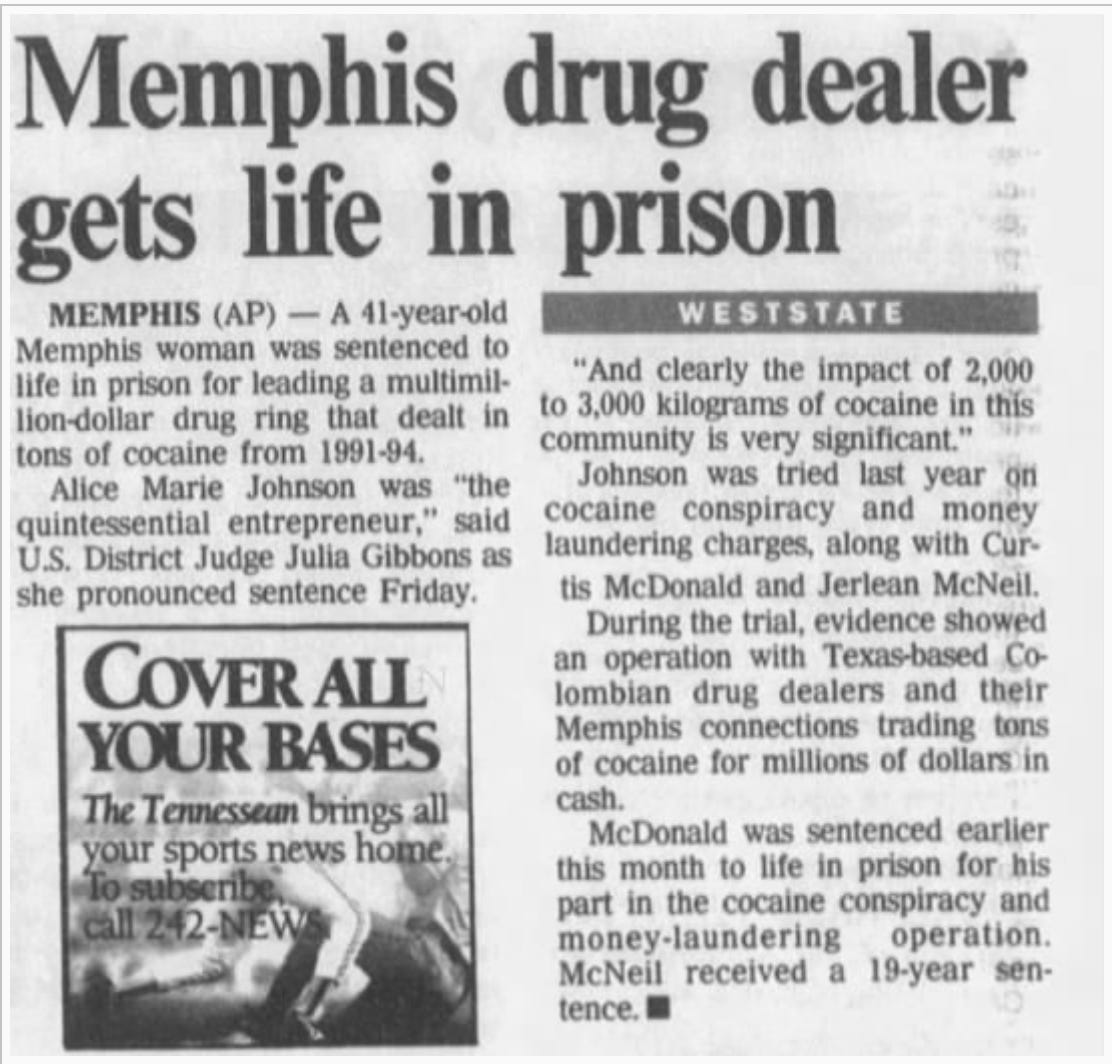

Above: Alice Marie Johnson, “first-time drug offender,” ran a massive cocaine operation worth millions of dollars, with ties to a Colombian drug cartel

I read David French’s missive from The Dispatch this past Sunday and, as often happens when I read his pieces about crime and/or race, I found myself questioning some of his claims—and in particular the evidence he cited to support them.

I spent some time following some of the links he provided to underpin his assertions about institutional racism in the criminal justice system, and I found much of the supporting evidence to be partisan, lazy, and biased.

Let me start with a point of agreement and an important caveat: I admire David French. He is smarter than I am. He is more knowledgeable about many aspects of the law than I am—although, I’d guess, that’s not true of criminal law. (Hey, even really smart people can’t be experts on everything!) And he has a pleasant manner in responding to his critics, which is something I admire and try to emulate . . . when I remember to. Accordingly, any time I criticize him, I think it’s important to remind people that I have a positive impression of the man. There is a certain contingent out there that is inexplicably malicious towards him. I am not one of those people, and I do not want to cultivate that audience. That said, when I have criticisms of anything important—including arguments made by people I like—I tend to voice them, and that’s largely what I’ll be doing today. As I do, keep in mind that the time and energy I spend doing so is a measure of my respect for French.

And although I am about to criticize him, I agree with some of what he said in his piece, so I’d like to start with that.

Where French and I Agree

French says:

Last month, The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf wrote an important essay arguing that “under-policing is a form of oppression too.” Combine criminal activity with absent or ineffective police, and you have a formula not just for death and destruction but for pervasive fear and economic decline.

In one of his most telling paragraphs, Friedersdorf noted how easy it is [to] get away with murder in the United States of America, especially if the victim is black:

The Murder Accountability Project, a nonprofit watchdog group that tracks unsolved murders, found in 2019 that “declining homicide clearance rates for African-American victims accounted for all of the nation’s alarming decline in law enforcement’s ability to clear murders through the arrest of criminal offenders.” In Chicago, the public-radio station WBEZ’s analysis of 19 months of murder-investigation records showed that “when the victim was white, 47% of the cases were solved … For Hispanics, the rate was about 33%. When the victim was African American, it was less than 22%.” Another study in Indianapolis found the same kind of disparities.

These are stunning numbers. The failure to solve murders and hold murderers accountable not only breeds lawlessness, it creates a profound, independent moral injury. One of the first sins recorded in scripture is Cain’s murder of Abel, an act that caused God to say to Cain, “What have you done? The voice of your brother's blood is crying to me from the ground.”

It is absolutely the case that the failure to hold accountable murderers of young black men is a moral injury, and it’s one I have fought my whole professional life. I have tried (if my math is correct) 37 murder cases in my career. Most of those were gang cases where the victim was not necessarily what most people would consider an upstanding member of society. This never mattered to me. I always applied the Harry Bosch principle: “Everybody counts or nobody counts.” I even cited that line in closing arguments. I worked hard on these cases. I came to court prepared. I lost sleep. I got good results. That work mattered. I had more than one mother of a victim tell me that she had changed her mind about law enforcement after she saw the way that detectives and I had worked to get justice for her murdered child. Nothing could mean more to me.

Some of these victims were white, some were Hispanic, some were Asian, and some were black. That, too, never mattered—any more than whether the victim had a criminal record. Nobody deserves to be murdered. Every murderer must be held accountable—if the evidence is there, and if accountability can be found within the bounds of our system of laws and ethics.

And in many ways, it seems, nothing could mean less to Big Media than murders in minority communities. Long-time readers of my blog know the crusade I fought to get some kind of attention directed to the murder of Quanisha Pitts, an innocent teenage black girl in Compton who was gunned down at the end of a date. It just so happened that this murder took place around the same time that Paris Hilton—a very rich and very famous white girl—went to jail for a few days due to a probation violation on a DUI. See if you can guess which of these two stories—Paris Hilton or Quanisha Pitts—absolutely entranced the Very Serious and Very Liberal Bastion of Serious Journalism That Is Serious, aka the L.A. Times. You can check out my posts from 2007 (14 years ago!) by clicking this link and browsing through the various entries, but the bottom line is that there were at least a dozen stories about Paris Hilton in Los Angeles’s Very Serious Paper of Record, and approximately, oh, say, zero stories about Quanisha Pitts in the print edition. I learned about Pitts’s murder from reading the excellent Homicide Blog by the Times’s Jill Leovy. There was a section from Leovy’s entry that I quoted in this blog post:

Martin and two of his neighbors, who soon join the conversation, believe murders in Compton in particular get short shrift. They are disturbed in ways that they struggled to articulate by the way media outlets treat stories about the killings of their city’s men and women.

“It’s the way you report it,” said Martin’s neighbor, military reservist Walt Graham, 53, (near left, above) who came over from his front yard. “It’s just going to be someone killed in Compton, on page 25,” he said.

“Just another story. Another minority kid. So what.”

Ah, Walt Graham, how naive you were to think Quanisha Pitts’s murder would be reported on page 25. It was never in the print edition at all. It was on page f*** you we don’t care. It still makes me angry, all these years later.

Leovy, as it happens, went on to write an excellent book titled Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America. I highly recommend it. The book makes the same point I have just been making here: that a key component to building the black community’s trust in law enforcement is to treat murders that happen there with the utmost seriousness.

So that’s one place where I agree with David French. Let’s get to where we disagree.

Incarceration Significantly Reduces Crime

French says:

[T]he smartest conclusions have determined that rapid increases in incarceration are not in fact principally or even significantly responsible for declines in American crime, and they have long passed the point of diminishing marginal returns. A 2012 Brennan Center for Justice paper found that “increased incarceration has been declining in its effectiveness as a crime control tactic for more than 30 years. Its effect on crime rates since 1990 has been limited, and has been non-existent since 2000.”

I don’t want to oversell this point. It’s not that increased incarceration has no effect on American crime, just that that effect has been increasingly marginal. At the same time, however, it has an immense impact on the millions of Americans who are caught up in the system itself, either as prisoners or as their children, spouses, or parents. The effects on family formation and lifetime earning potential are catastrophic, for example, and can lead to enduring cycles of poverty and inequality.

There’s a link, so let’s follow it and see what the “smartest conclusions” say. First—and I don’t want to get all ad hominem here, and believe me I will be exploring the claims themselves—but let’s just take a moment to educate ourselves on what the “Brennan Center for Justice” is. Who is the “Brennan” in the title of the organization, which claims to be “[i]nspired by Justice William J. Brennan Jr.'s devotion to core democratic freedoms”? Why, that would be William Brennan, one of the most rabidly partisan leftist Supreme Court Justices in history, who is perhaps most famous for his devotion to the Rule of Law. [Enter an aide from stage right who whispers in Patterico’s ear and hands him a note card.] Hold the fort! Says here I have it all wrong: Brennan didn’t care about the Rule of Law at all! I guess I was thinking of his support for a different rule, called the Rule of Five: “A five-justice majority on the Court, the strong Rule of Five asserts, can do anything, at least in deciding constitutional law cases.” In other words—and I think this is a fair summary of William Brennan’s “judicial philosophy,” to the extent that you want to glorify his naked power grabs with such a phrase—”I don’t really care what the Constitution actually says; if five of us Supreme Court justices can agree, we can make it say whatever we want it to say.”

That’s the fella who inspired the “Brennan Center for Justice.” But by all means, let’s hear them out on their potentially very meritorious arguments about how locking up criminals barely prevents crime. Their report assumes that having criminals on the street would be a net economic benefit:

One of the great problems we face today is mass incarceration, a tragedy which has been powerfully documented. . . This prodigious rate of incarceration is not only inhumane, it is economic folly. How many people sit needlessly in prison when, in a more rational system, they could be contributing to our economy?

Did the folks at the Brennan Center for Justice ever consider that people who commit crimes might be, on balance, a net cost rather than benefit to society? They do actually ask the question! But they don’t really answer it. What they do instead is argue that “continuing to incarcerate more people has almost no effect on reducing crime.” Their main finding, to me, elides the question of the detrimental effect that criminals’ crimes have on society, and instead engages in a sort of misdirection act, focusing on the (to me) obvious truth that “incarceration has ‘diminishing marginal returns’” . . . which means that, like any policy tool, “incarceration becomes less effective the more it is used.”

Is this really such a revelation? Doesn’t any variable decrease in effectiveness the more it is used?

Their big takeaway, as I read the following chart, is that crime decreased dramatically as incarceration increased dramatically, but then even greater incarceration led to diminishing returns—a contention that I think would not surprise any economist familiar with the age-old concept of diminishing marginal returns:

This is not a finding that locking people up doesn’t work—and even the lefty Brennan folks admit this:

To be clear, this report does not find that incarceration never affects crime. Incarceration can control crime in many circumstances. But the current exorbitant level of incarceration has reached a point where diminishing returns have rendered the crime reduction effect of incarceration so small, it has become nil.

Ultimately, without spending thousands more words on this analysis, the lefties perform a fancy regression analysis that basically says that incarceration and police work have had a big effect on crime, but so did the increase in income from an improved economy, as well as other factors. I don’t particularly quibble with the findings . . . as fairly stated. But let’s not overstate the findings.

To be fair, French largely reports these findings accurately, but I think he overshoots the proof when he says “rapid increases in incarceration are not in fact principally or even significantly responsible for declines in American crime.” The fact that incarceration has diminishing marginal returns, and that an improving economy and other societal factors can have a significant effect on crime rates, does not mean that an increase in the rate of incarceration cannot “significantly” contribute to reductions in crime—especially when that increase follows a period of too-lenient punishment for violent crime. I have seen a lot of people in the system who committed murders and other serious crimes in the 1980s and got a slap on the wrist—and then turned up committing violent crimes again. Does this come as a surprise to anyone with common sense? Does anyone think that giving real punishment to murderers does not prevent more murders?

About Those Vast Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System

French also argues:

And that’s without even addressing the vast racial disparities in both incarceration and sentencing. There is no question that America has progressed past the worst days of an thoroughly and explicitly racialized justice system, but it is still true that not only are black and Hispanic men far more likely to be imprisoned than white men, there is a disturbing amount of evidence that they’re often charged with more severe crimes than similarly situated whites.

Let’s click on that “vast racial disparities” link and see where it leads, shall we? We soon learn that it leads to a “Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System” by something called the “Sentencing Project.” What is that organization?

Established in 1986, The Sentencing Project works for a fair and effective U.S. criminal justice system by promoting reforms in sentencing policy, addressing unjust racial disparities and practices, and advocating for alternatives to incarceration.

Just in case you thought they were coming at this from a neutral perspective: they are not. But let’s look at their evidence. As we see a link to validate a claim, we’ll follow that link and see what it says. And when that link depends on another, we’ll click the second link too! And so on, and so on, and so on.

In 2016, black Americans comprised 27% of all individuals arrested in the United States—double their share of the total population. Black youth accounted for 15% of all U.S. children yet made up 35% of juvenile arrests in that year. What might appear at first to be a linkage between race and crime is in large part a function of concentrated urban poverty, which is far more common for African Americans than for other racial groups. This accounts for a substantial portion of African Americans’ increased likelihood of committing certain violent and property crimes. But while there is a higher black rate of involvement in certain crimes, white Americans overestimate the proportion of crime committed by blacks and Latinos, overlook the fact that communities of color are disproportionately victims of crime, and discount the prevalence of bias in the criminal justice system.

(My bold type.) The first thing I ask when people or organizations make claims about racial “disparities” in crime statistics is: do we know the disparity is because of race, or could it be explained by something else? Regular readers of this newsletter know that I have been at pains to show, for example, that the “disproportionate” percentage of police shootings of blacks happens to match up quite neatly to the disproportionate share of fatal attacks on police officers committed by blacks.

Here, in language I have placed in bold, the Sentencing Project acknowledges that “there is a higher black rate of involvement in certain crimes.” The authors try to take the sting out of this observation by throwing out mainly irrelevant observations—such as Americans’ overestimation of the proportion of crime committed by minorities, or the very true observation that minorities are disproportionately crime victims. But these observations do nothing to explain why there is a “higher black rate of involvement in certain crimes.” The Sentencing Project then makes an allegation about the “prevalence of bias in the criminal justice system.” Now we’re getting somewhere! What is the evidence for that? We read on.

The report says that “[t]he rise of mass incarceration begins with disproportionate levels of police contact with African Americans.” Again, we have a chicken-and-egg issue here. Yes, police tend to go where the crime is, and often the crime happens in poorer neighborhoods—and many of those neighborhoods are minority neighborhoods. (Ironically, a greater police presence in minority neighborhoods is one of the things French recommends in his article! And I agree.) But where is the evidence that blacks are committing crime at the same levels, but being stopped more? After we bypass complaints about the drug war and quotes of a finding from a Clinton-appointed judge, we finally get to some actual numbers-driven claims about disparities:

In recent years, black drivers have been somewhat more likely to be stopped than whites but have been far more likely to be searched and arrested. The causes and outcomes of these stops differ by race, and staggering racial disparities in rates of police stops persist in certain jurisdictions—pointing to unchecked racial bias, whether intentional or not, in officer discretion. A closer look at the causes of traffic stops reveals that police are more likely to stop black and Hispanic drivers for discretionary reasons—for “investigatory stops” (proactive stops used to investigate drivers deemed suspicious) rather than “traffic-safety stops” (reactive stops used to enforce traffic laws or vehicle codes). Nationwide surveys also reveal disparities in the outcomes of police stops. Once pulled over, black and Hispanic drivers were three times as likely as whites to be searched (6% and 7% versus 2%) and blacks were twice as likely as whites to be arrested. These patterns hold even though police officers generally have a lower “contraband hit rate” when they search black versus white drivers.

I was interested in the claim in the last sentence, so I checked out the footnote to see the source. It is:

Harris, D. (2012). Hearing on “Ending Racial Profiling in America,” Testimony of David A. Harris. United States Senate Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Human Rights. (p. 8).

Great! So now we click on that, and it takes us to congressional testimony from a University of Pittsburgh School of Law professor named David Harris. Professor Harris delivers a history of racial profiling in America, which he divides into three waves. I got caught up in his description of the so-called “first wave”:

The first wave had its roots in the 1980s and the War on Drugs. During the 1980s, federal law enforcement authorities concluded that efforts aimed at drug interdiction on commercial aircraft had caused traffickers to begin transporting more of their product in cars and trucks, primarily on interstate highways. To meet this challenge, the federal government began Operation Pipeline, a national law enforcement campaign that trained thousands of state and local police officers in drug interdiction methods for use against vehicles. By the early 1990s, drug interdiction units had become common in state, county, and municipal police departments all over the country. Among the best known of these interdiction efforts were the actions of the New Jersey State Police, which targeted blacks and Latinos on the New Jersey Turnpike, and the Maryland State Police’stargeting of blacks on Interstate 95.

Hmm. The actions of New Jersey State Police, and whether they actually profiled people on the New Jersey Turnpike, is a topic I actually know something about. But let’s see what Professor Harris has to say about it. As authority for the notion that there was racial profiling on the New Jersey Turnpike, he cites this case in footnote 4:

State v. Pedro Soto, 734 A. 2d 350 (N.J. Super. Ct. Law Div. 1996).

So: we go searching for that decision, and learn that in 1996, a judge found a prima facie case of selective enforcement of traffic laws on the New Jersey Turnpike, based on a comparison of a database of stops with an experiment conducted under the supervision of one “Fred Last, Esq., of the Office of the Public Defender.” Sounds unbiased to me! The state’s expert in that case attempted to rebut the study by noting that the claim of selective enforcement did not adequately address the possibility that black drivers were in fact speeding more than white drivers. The court pointed to the lack of studies addressing that question, rather dismissively characterizing the state’s expert’s concession that “he knew of no study indicating that blacks drive worse than whites.” (The issue was not whether they drive “worse,” as the court tendentiously put it, but whether they speed more often.) In particular, the state’s expert wanted to know who was going the fastest while speeding, since it is well known that most people speed, but that the people who get pulled over are those who drive the fastest. If you’re doing 82 in a 65 mph zone, you’re more likely to be pulled over than the guy doing 72 even though you’re both speeding. But the court rejected this line of reasoning, arguing in part that the state’s expert “was unclear, though, how he would design a study to ascertain in a safe way the vehicle going the fastest above the speed limit at a given time at a given location and the race of its occupants without involving the credibility of State Police members.”

As you may have guessed, the issue did not end there. Based in part on the assumption that blacks and whites drive at the same speeds, the Clinton Justice Department started coercing consent decrees governing police agencies who were thought to be racially profiling. I’ll turn the microphone over to Heather MacDonald to explain what happened next:

Faced with constant calumny for their stop rates, the New Jersey troopers asked the attorney general to do the unthinkable: study speeding behavior on the turnpike. If it turned out that all groups drive the same, as the reigning racial profiling myths hold, then the troopers would accept the consequences.

Well, we now know that the troopers were neither dumb nor racist; they were merely doing their jobs. According to the study commissioned by the New Jersey attorney general and leaked first to the New York Times and then to the Web, blacks make up 16 percent of the drivers on the turnpike, and 25 percent of the speeders in the 65-mile-per-hour zones, where profiling complaints are most common. (The study counted only those going more than 15 miles per hour over the speed limit as speeders.) Black drivers speed twice as much as white drivers, and speed at reckless levels even more. Blacks are actually stopped less than their speeding behavior would predict—they are 23 percent of those stopped.

The devastation wrought by this study to the anti-police agenda is catastrophic. The medieval Vatican could not have been more threatened had Galileo offered photographic proof of the solar system. It turns out that the police stop blacks more for speeding because they speed more. Race has nothing to do with it.

That’s my bold emphasis. Now, the career attorneys in the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department didn’t like those results, and if you ever bring them up, people will cite their claim that the study was not reliable. But the methodology seems sound to me:

The study, which was done between March and June 2001, matched photographs of drivers taken by special cameras with radar-gun readings of their speed along 14 locations on the turnpike.

Three people scored each picture independently, and made a decision on ethnicity. At least two evaluators agreed on 26,334 of the drivers, said Robert Voas, senior research scientist at the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation.

The ethnic makeup was nearly identical to a study done a year earlier in which motorists identified their own ethnic makeup, he said.

"That gave us more confidence in our results," Voas said.

MacDonald’s article goes on to describe the rather comical arguments of the DOJ lawyers in support of their attempts to suppress the study. They complained that two of three evaluators agreeing on race was not good enough; it had to be unanimous. So the study’s authors reanalyzed the numbers using only photos that all three evaluators had agreed on, and the numbers didn’t change. DOJ complained about the unreadable photos, but could not justify why the racial statistics would be changed by the unreadable photos. Finally the study’s authors suggested that the study be put through a peer-review process. DOJ opposed that. A co-author of the study said: “I think it’s very unfortunate that the politics have gotten in the way of science.”

Now: all of this evidence was available in 2002. Yet our Professor Harris, the guy who pontificated about racial profiling on the New Jersey Turnpike to a congressional subcommittee in 2012, says not one word about the New Jersey study that dispelled the racial profiling claims . . . even as the professor cites court cases from 1996, based on studies supervised by a public defender, to support his claims of racial profiling.

It should be clear by now that Professor Harris is not a reliable source.

But remember: we followed the link to Professor Harris’s testimony for a different (if related) reason: to see the basis for the Sentencing Project’s claim that “police officers generally have a lower ‘contraband hit rate’ when they search black versus white drivers”—which, we are told, proves the hypothesis that racial profiling is happening everywhere. Here is what Professor Harris says about that:

In the late 1990s, data on police practices such as traffic stops and stop and frisk practices began to become available for the first time. These data often became public as a result of legal actions (such as law suits against the New Jersey State Police and the Maryland State Police) or government inquiries (e.g., the New York State Attorney General’s probe of stop and frisk practices following the shooting of Amadou Diallo by four New York Police Department officers). The data allowed researchers to answer two related questions. First, did the police departments in question use race or ethnic appearance as one factor to target suspects? Second, if the department was engaged in racial or ethnic targeting, did using this tactic increase the “hit rate”—the rate at which officers found drugs or guns, or made arrests? The data showed that, for the police departments studied, blacks and Latinos were, indeed, targeted using race or ethnic appearance as one factor. The data simply did not support any other possible explanation (e.g., witnesses reporting more minority perpetrators, or heavy police deployment in high-crime minority neighborhoods). As for hit rates, when the data were disaggregated to show the hit rates police attained when targeting blacks and Latinos, as opposed to when they stopped, searched, and arrested whites, hit rates for the minority groups were not higher than hit rates for whites; they were not the same as the hit rates for whites. The hit rates for blacks and Latinos were actually lower—measurably lower, by a statistically significant amount—than the hit rates for whites. Using racial or ethnic appearance made police not more accurate and efficient, but less.

The italics are in the original; the bold is mine, for reasons that will become clear shortly.

It’s difficult to assess the professor’s claim, as no working link to a study is provided. However, there is a simple potential explanation for higher contraband hit rates for whites than for Latinos or blacks—an explanation that Professor Harris does not bother to discuss. Namely: when people are arrested after a vehicle stop, their car is going to be searched incident to arrest even if the arresting officer does not suspect they have contraband. So, for example, if a Hispanic driver is arrested for driving on a suspended license, or a black driver is arrested because he has a warrant out for his arrest, those drivers’ cars are going to be impounded and searched as part of a routine inventory search, even if the officer has no reason at all to believe the arrested individual had contraband. If certain groups are arrested more often, because they commit more crime, they will be searched more. This is why I bolded the language about motorists being “arrested”—it makes clear that Professor Harris is not talking merely about consent searches.

Thus, for example, in a 2016 report from Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt, we find one potential explanation for higher contraband hit rates among whites being the higher arrest rates for blacks and Hispanics:

The "contraband hit rate" reflects the percentage of searches in which contraband is found. Contraband was found in 32.3% of all searches that were conducted in 2016. There is some variation, however, in the contraband hit rate across race and ethnic groups. The contraband hit rate for whites was 33.9%, compared with 29.0% for Blacks and 25.3% for Hispanics. This means that on average searches of African-Americans and Hispanics are less likely than searches of Whites to result in the discovery of contraband. This difference may result in part from the higher arrest rates for African-Americans and Hispanics, circumstances that compel a search.

Why are blacks and Hispanics being arrested more often? Because they commit more crimes. All of this is consistent with what Heather MacDonald explains in a different piece:

According to driver self-reports, blacks and Hispanics were more likely to have their persons or cars searched than white drivers, and were more likely to be subjected to the threat or use of force by the officer who stopped them. The survey defines force as pushing, grabbing, or hitting; a typical force incident, characterized by the survey respondent as “excessive,” consisted of an officer grabbing the respondent by the arm as he was fleeing the scene and pushing him against his car. Specifically, black drivers said that they or their cars were searched 10.2 percent of the time following a stop, Hispanic drivers 11.4 percent of the time, and white drivers 3.5 percent of the time. As for police threats or use of force, 2.4 percent of Hispanic drivers, 2.7 percent of black drivers, and 0.8 percent of white drivers claimed that force had been threatened or used against them.

None of these findings establishes prejudicial treatment of minorities. The Times, for instance, does not reveal that blacks and Hispanics were far more likely to be arrested following a stop: Blacks were 11 percent of all stopped drivers, but 24 percent of all arrested drivers; Hispanics, 9.5 percent of all stopped drivers, but 18.4 percent of all arrested drivers; and whites, 76.5 percent of all stopped drivers, but 58 percent of arrested drivers. The higher black and Hispanic arrest rates undoubtedly result from their higher crime rates. The national black murder rate, for example, is seven times higher than that of all other races combined, and the black robbery rate eight times higher. Though the FBI does not keep national crime data on Hispanics, local police statistics usually put the Hispanic crime rate between the black and white crime rates. These differential crime rates mean that when the police run a computer search on black and Hispanic drivers following a stop, they are far more likely to turn up outstanding arrest warrants than for white drivers.

These higher arrest rates in turn naturally result in higher search rates: Officers routinely search civilians incident to an arrest. Moreover, the higher crime rates among blacks and Hispanics mean a greater likelihood that evidence of a crime, such as weapons or drugs, may be in plain view, thereby triggering an arrest and a search.

(My bold.) What I have offered here is just a smattering of information I found by clicking the links in French’s piece, following those links to other links (and more links and even more links) and then providing a critical analysis of what I have found. Nothing I say here proves there is no racism in the justice system; since racism persists in the United States, it certainly must be present in some measure in all of our institutions. But we are entitled to question just how pervasive that is . . . and whether bias, sloppy reasoning, and a failure to consider alternate causes undermines the strength of some of the evidence submitted in service of narratives of overwhelming institutional racism in the criminal justice system.

Alice Johnson: First-Time Drug Offender?

I can’t end this newsletter without commenting on French’s description of Alice Johnson:

I’ll be honest, I’ve got a bit of a personal connection to this conversation, a connection that I’d never had before. In 2019 my wife was blessed to work with Alice Johnson on her autobiography, After Life. Johnson, readers may remember, was a first-time drug offender who was sentenced to life in prison at the height of the war on drugs. Donald Trump granted her clemency (and later pardoned her) after Kim Kardashian pleaded her case in the White House. It was one of Trump’s best moments in office.

Alice stayed at our house for a short time while she finished her book, and our conversations helped teach me that there is a tremendous need for an interfaith, cross-partisan coalition of Americans who can see that crime imposes real costs on communities, while also understanding that vengeance and mass incarceration is toxic to the culture and soul of a nation.

The description of Alice Johnson as a “first-time drug offender”—with literally no other description of her crimes—is a rather remarkable whitewashing. I had never looked at Johnson’s case before, having swallowed the propaganda about her being a first-time offender who made “one mistake”—until I ran across a description of her case in a book I am reading titled Frankly, We Did Win This Election: The Inside Story of How Trump Lost, by Michael Bender:

Johnson had spent more than two decades behind bars after running a multimillion-dollar cocaine operation with ties to a Colombian drug cartel.

Whoa. That’s a bit more than being a “first-time drug offender,” isn’t it? Here’s how a contemporaneous article described Johnson’s conduct:

And it turns out that court documents bear out that Johnson’s conduct was far from a one-time mistake.

Life without the possibility of parole, in my judgment, is far too harsh a sentence for someone like Alice Johnson. By all accounts, she became a model prisoner. Pardoning her was inappropriate, in my view, but commuting her sentence would have been a perfectly appropriate thing to do. But let’s describe her conduct in a fair way that lets people understand what she really did.

Ultimately, if David French wants to convince me that systematic racism pervades the criminal justice system, he’s going to have to come up with better evidence than he provided last Sunday.

I still like him.

Hi Patterico, Been reading you for a decade or more. I always take away something when I engage with one of your essays. Just felt like it was time to pay the compliment. Please keep up the good work.

David French sucks.