An Error in Justice Gorsuch's Concurrence in the OSHA Vaccine Mandate Case

The Justice claimed OSHA took a past position that the agency did not actually take.

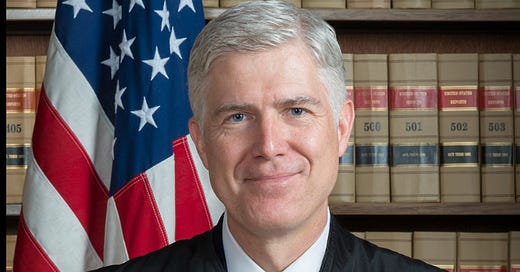

Recently, I was preparing a summary of the Supreme Court’s decision in the OSHA vaccine mandate case (as well as the related CMS decision) when I noticed something odd. In his concurrence in the OSHA case, Justice Gorsuch cited a brief from OSHA in order to claim that OSHA had taken a position in 2020 that supported the majority’s position in the OSHA case.

The problem is, Justice Gorsuch was wrong. OSHA did not argue the position that Justice Gorsuch claims OSHA argued.

I will not fully summarize the case in this newsletter; subscribers can read that summary later this week. (Spoiler alert: although I am a constitutional conservative and am typically persuaded by the Court’s conservatives, I found the majority opinion in the OSHA case entirely at odds with logic.) Today, I want to concentrate on Justice Gorsuch’s error.

First, let’s provide some context and background. The dissent argues that the vaccine/testing mandate is similar to regulating other hazards, like fire, that are present both inside and outside the workplace. The majority responds to that argument as follows:

The dissent contends that OSHA’s mandate is comparable to a fire or sanitation regulation imposed by the agency. See post, at 7–9. But a vaccine mandate is strikingly unlike the workplace regulations that OSHA has typically imposed. A vaccination, after all, “cannot be undone at the end of the workday.”

This is a central point, because the dispute over whether COVID is a “workplace” hazard or a general health hazard lies at the very heart of the disagreement between the majority and the dissent.

In his concurring opinion, Justice Gorsuch expands on the majority’s argument that “a vaccination . . . cannot be undone.” Justice Gorsuch claims that OSHA itself recently conceded that it lacks authority to issue regulations that “affect workers’ lives outside the workplace”:

As the agency itself explained to a federal court less than two years ago, the statute does “not authorize OSHA to issue sweeping health standards” that affect workers’ lives outside the workplace. Brief for Department of Labor, In re: AFL–CIO, No. 20–1158, pp. 3, 33 (CADC 2020). Yet that is precisely what the agency seeks to do now—regulate not just what happens inside the workplace but induce individuals to undertake a medical procedure that affects their lives outside the workplace.

Note that the phrase “affect workers’ lives outside the workplace” is not in quotes; this is Justice Gorsuch’s paraphrase of what he claims was OSHA’s position in 2020, when it filed a brief in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. I decided to look up the brief itself to see if his description is accurate.

It is not.

You can read the brief, which I pulled off of PACER, here. The dispute in the case centered on an effort by the AFL-CIO to force OSHA to issue an Emergency Temporary Standard, or ETS, to protect workers from COVID. An ETS is a mechanism that allows OSHA to impose a mandatory standard on employers in emergency situations without the usual notice and comment process that agencies must typically follow before their regulations may take effect. The vaccine/testing mandate at issue, which was issued by OSHA during the Biden administration, was issued under the authority of an ETS.

In 2020, OSHA did not yet believe that a COVID-related ETS was necessary, and it resisted the AFL-CIO’s efforts to impose one on the agency against its own judgment. OSHA filed a brief with the D.C. Circuit, advancing many of the typical arguments an agency raises when its discretion is challenged. For example, OSHA argued that the AFL-CIO lacked standing, and argued further that its own determinations are subject to deference.

OSHA also opposed the ETS by advancing several arguments specific to the pandemic.

First, OSHA said that employers were already required — both by existing regulations and by the “general duty clause” of the Occupational Safety and Health Act — to take precautions against COVID-19.

OSHA also argued that the proposed ETS would be counterproductive to OSHA’s ongoing efforts against the pandemic. Specifically, OSHA argued that the state of knowledge about COVID was always in flux and that new information often became available rapidly. Cementing OSHA’s reaction in an ETS would deprive OSHA of needed flexibility to adapt to new information.

In the section of the brief devoted to portraying the ETS sought by the AFL-CIO as potentially counterproductive, OSHA’s lawyers wrote the following passage, which contains emphasis by me in bold type:

Finally, to the extent the ETS petition is even broader, asking OSHA to issue a sweeping infectious disease standard beyond COVID-19, the ETS petition does not identify a specific workplace-related grave danger that can permissibly be addressed by an ETS. A “grave danger” is a degree of risk higher than the “significant risk” required to promulgate a permanent safety and health standard under Section 6(b) of the OSH Act. Compare Indus. Union Dep’t, AFL-CIO v. Am. Petroleum Inst., 448 U.S. 607, 639 (1980) (permanent standard), with Dry Color Mfrs. Ass’n v. Dep’t of Labor, 486 F.2d 98, 104-05 (3d Cir. 1973) (ETS). As explained in OSHA’s Denial Letter, AFL-CIO has not provided compelling evidence that an undefined category of “infectious diseases” pose a grave and urgent threat to workers. Denial Letter, Addendum Tab 2, at 1. The OSH Act does not authorize OSHA to issue sweeping health standards to address entire classes of known and unknown infectious diseases on an emergency basis without notice and comment. Cf. AFL-CIO v. OSHA, 965 F.2d 962, 972 (11th Cir. 1992) (vacating standard that regulated hundreds of “diverse” airborne substances without “substantial evidence in the record” to support the regulation of each).

The quote provided by Justice Gorsuch in his concurrence is a partial quotation of the above paragraph. But OSHA did not argue its brief that (to quote Justice Gorsuch) that

the statute does “not authorize OSHA to issue sweeping health standards” that affect workers’ lives outside the workplace.

Instead, OSHA argued this (again my emphasis):

The OSH Act does not authorize OSHA to issue sweeping health standards to address entire classes of known and unknown infectious diseases on an emergency basis without notice and comment

The point of this entire paragraph in OSHA’s 2020 brief, and the specific import of the “sweeping health standards” quote in that paragraph, is to respond to a possible argument seeking an ETS, not merely governing COVID, but also governing undefined classes of infectious disease. OSHA is trying to forestall any possible effort by the AFL-CIO to force OSHA “to issue a sweeping infectious disease standard beyond COVID-19” by arguing that there is no evidence that an “undefined category of ‘infectious diseases’” poses a “grave and urgent threat to workers.” Thus, OSHA argues, there could be no authority for an ETS that would impose on employers “sweeping health standards to address entire classes of known and unknown infectious diseases.” (All bold type is mine.)

Contrary to Justice Gorsuch’s fictional paraphrasing of OSHA’s position, none of this even remotely concerns the issue of whether the “sweeping health standards” (to use Gorsuch’s phrase) “affect workers’ lives outside the workplace.” Not only is that not what OSHA said, there is no plausible construction of that language by which a reasonable reader could even argue that OSHA said what Justice Gorsuch claims they said. Justice Gorsuch’s characterization is pure fiction, with literally no basis in OSHA’s brief, whatsoever.

I’m not going to say Justice Gorsuch “made this up,” or that he is “lying.” Again: I am a constitutional conservative who has considerable respect for Justice Gorsuch — and in any event, I try not to call people liars unless the evidence of intentional dishonesty is very clear.

I will say, however, that Justice Gorsuch’s characterization of OSHA’s position is an error. It is not just inaccurate; it is a mistake at best. Again, this is not a debatable point. Justice Gorsuch might personally believe that the Occupational Safety and Health Act does not authorize OSHA to issue standards that affect workers’ lives outside the workplace. But he has no basis whatsoever for attributing that view to OSHA, based on the brief they filed in the D.C.Circuit in 2020.

This is not the kind of thing that is easy to explain to journalists. But lawyers who care about the outcome of this case, who understand what I am saying here, should help put pressure on Justice Gorsuch to correct this error. His statement is simply not a fair reading of the document he cites, and it ought not remain in the official record.

COMING SOON FOR SUBSCRIBERS: my analysis of the OSHA decision as well as a few words about the CMS decision.

So why phrase this as a 'mistake'? Clearly it's an effort to misquote the OSHA response in order to claim expert evidence for his concurring opinion where none exists. If I turned that in as an undergraduate it would have meant an F. But this court is failing America at every turn so why not expect them to lie about the sources of their data?

Questions: Did the other Justices know this? And if so, don’t they have an obligation and responsibility to make the “mistake” known? If they didn’t or don’t know, why not? Don’t they have an equal obligation and responsibility to know this through researching and/or checking any claims presented by their colleagues as fact from the bench?